How does the client present credentials? (cookie vs header vs proof-of-possession)

How does the server validate those credentials? (lookup-based vs locally verifiable)

What’s your browser threat model? (Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) vs Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) changes everything)

How do you express permissions? (scopes, roles, attributes, relationships — and where you enforce them)

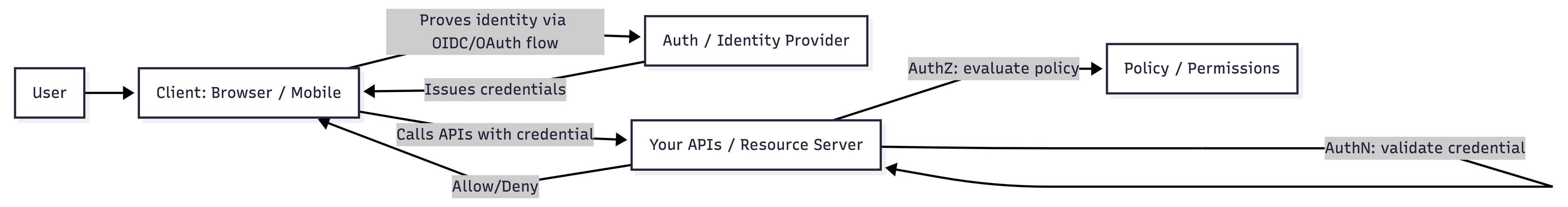

Authentication and Authorization

1) Introduction: AuthN vs AuthZ

Authentication (AuthN) answers: “Who is this?” It’s about establishing an identity: user, service, device, or workload.Authorization (AuthZ) answers: “What is this identity allowed to do?” It’s about enforcing policy on every sensitive action: data access, privileged operations, cross-tenant boundaries.This boundary matters because the industry’s biggest real-world incidents are usually authorization mistakes, not “login button doesn’t work.” Open Worldwide Application Security Project(OWASP) ranks Broken Access Control as a top risk category, and also highlights Identification & Authentication Failures as a major category.

2) Authentication deep dive

This part answers one production question:

How does a request prove identity safely, repeatedly, and revocably—across browsers, servers, mobile, and APIs?

2.1 Validation patterns

Pattern A: Lookup-validated credentials (stateful validation)

The server (or shared component) must look up something to validate the request.Mechanism examples:

Session identifier → look up session in Redis/DB

Opaque access token → introspect/lookup token metadata

Properties:

Fast revocation (delete/disable the record)

Central control (store MFA state, device/risk signals)

Requires shared storage or introspection path at scale

Pattern B: Self-contained signed credentials (locally verifiable)

The server can validate the request locally by verifying a signature + claims.Mechanism examples:

JWT access token verified via issuer keys (JWKS)

Properties:

Great for distributed systems (no per-request lookup)

Revocation is harder (short TTL + rotation/deny-lists/introspection)

Nuance: “stateless” is never absolute. Even with locally verified JWTs you still need key rotation, issuer trust, audience checks, clock skew handling, and an incident revocation plan.

2.2 How the client presents credentials

There are two dominant transports:

A) Cookies (automatic send by browser)

Browser automatically attaches cookies to matching requests.

This is convenient, but it changes your threat model:

CSRF risk exists because the browser will send credentials even if a malicious site triggers the request.

Best practice baseline: HttpOnly, Secure, and a thoughtful SameSiteposture (often Laxby default for typical web apps).

B) Authorization header (explicit send by code)

Client code attaches

Authorization: Bearer <token>to API calls.This avoids CSRF-by-default (because the browser won’t auto-add it), but increases exposure to:

XSS token theft if the token is stored in JS-accessible storage.

Bearer tokens are explicitly defined as “anyone who possesses it can use it,” which is why disclosure is such a big deal.

2.3 Client types: public vs confidential

OAuth/OIDC security depends heavily on whether your client can keep secrets.

Confidential client: can keep credentials safe (server-side apps, BFF, backend services)

Public client: cannot keep secrets (SPAs, mobile apps distributed to users)

This is why modern guidance pushes Authorization Code + Proof Key for Code Exchange (PKCE) for public clients.

2.4 OAuth 2.0 and OIDC (what token proves what)

OAuth 2.0 is a framework for authorization (delegated access).

OpenID Connect (OIDC) adds an authentication layer (identity), introducing the ID Token.

Three artifacts teams often confuse:

Authorization Code: short-lived code exchanged at

/tokenAccess Token: “Client is allowed to call API Z with permissions P.” (API authorization input)

ID Token (OIDC): “User authenticated at issuer X, for client Y, at time T.” (client-side identity)

2.5 OAuth 2.0 flows you should actually use (and the ones to avoid)

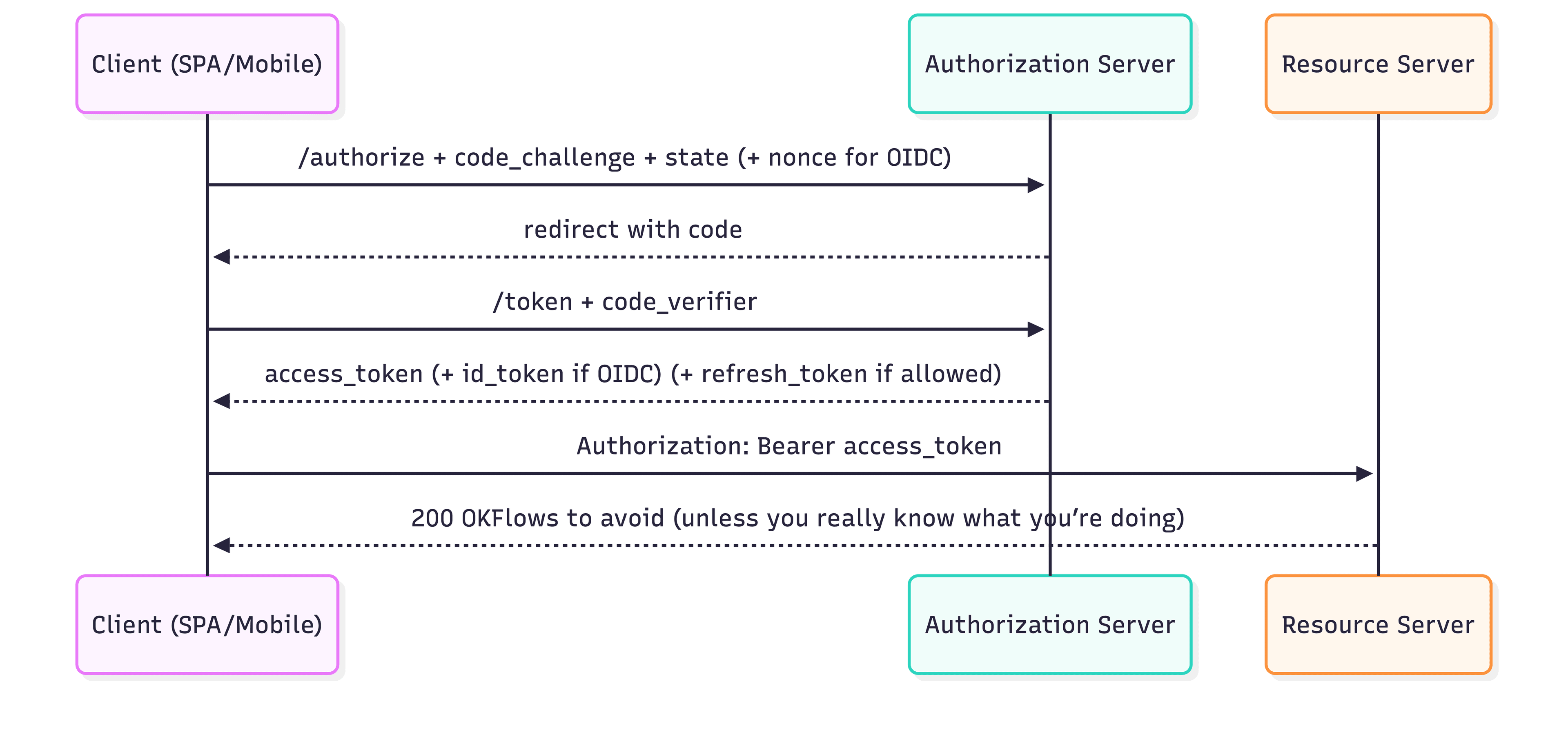

Default for browser + mobile in 2026: Authorization Code + PKCE

Public clients (SPA, mobile) can’t keep a client secret, so PKCE is the standard defense against authorization-code interception.

For native apps, best practice is to run the authorization request in the system browser (external user agent), not an embedded webview.

OAuth 2.0 flow

Implicit: explicitly discouraged/deprecated by modern OAuth security best current practice.

ROPC (Resource Owner Password Credentials): generally discouraged (turns your app into a password collector, breaks MFA/SSO posture).

2.6 Credential lifecycle: issue → store → renew → revoke

This is where “demo auth” becomes “production auth”.

Issuance

User authenticates (password/MFA/passkeys/social/enterprise)

Server issues credentials appropriate to client type and risk posture

Storage (where you put secrets matters)

A safe mental model:

Browser JS is a hostile environment once XSS exists.

If you can keep long-lived credentials out of JS, do it.

Common production approaches:

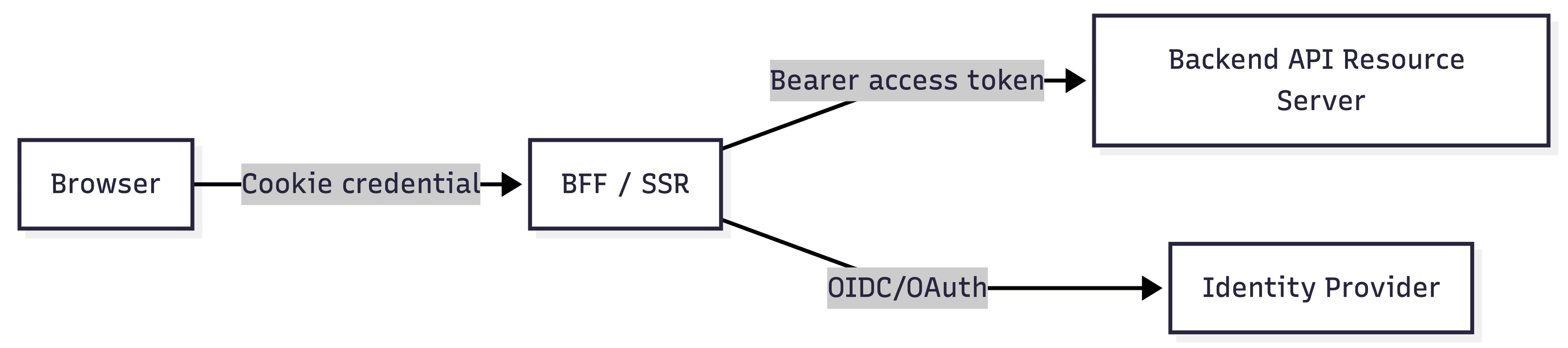

BFF/SSR: browser stores a cookie; server stores refresh tokens (and often access tokens) server-side.

SPA direct-to-API: access token in memory; refresh via safer mechanisms (or use a BFF-lite).

Renewal

Access tokens should be short-lived; refresh tokens allow UX without frequent logins.

Revocation

OAuth defines a token revocation endpoint standard. But revocation effectiveness depends on your validation pattern:

Lookup-validated credentials: revoke immediately by deleting/marking invalid

Locally verified JWT: revocation is not naturally immediate unless you add additional state (deny-list/introspection/short TTL)

2.7 Concrete implementation patterns

In real systems you often use a hybrid:

Browser ↔ Web app (BFF/SSR): a cookie-based credential (state stored/managed by the web app / IdP SDK)

Web app ↔ Backend APIs: a bearer access token (usually JWT) attached to API calls

That’s “stateful at the edge, stateless between services” (or “stateful control-plane, stateless data-plane”), and it’s extremely common in production.

concrete implementation patterns

Key idea: “stateful at the edge, stateless between services” (hybrid).

2.8 OAuth/OIDC production defaults: rotation, MRRT, cookie flags

Access tokens

Keep short-lived (e.g., 5–15 minutes) to reduce replay damage.

Refresh tokens

Treat as high-value secrets:

store hashed (server-side if possible)

rotate on use

implement reuse detection (revoke family / force re-auth)

define concurrency behavior (overlap window or single-flight refresh)

MRRT (Multi-Resource Refresh Token)

Convenient, but increases blast radius:

one refresh token can mint access tokens for multiple audiences/scopes

use only with strong controls (rotation, anomaly detection, tighter policies)

Cookie flags

HttpOnly: reduces XSS cookie theftSecure: HTTPS onlySameSite: reduces CSRF surface (defense-in-depth, not the only control)

2.9 Sender-constrained tokens (advanced, but worth knowing): DPoP and mTLS

Bearer tokens are replayable by definition. Two common “make replay harder” approaches:

DPoP(application-layer proof-of-possession): binds token usage to a client-held key; helps detect replay.

mTLS-bound tokens: binds tokens to a client certificate at the TLS layer.

Use when:

You’re in higher-risk environments (finance, regulated, high-value actions), or you need stronger guarantees than bearer tokens provide.

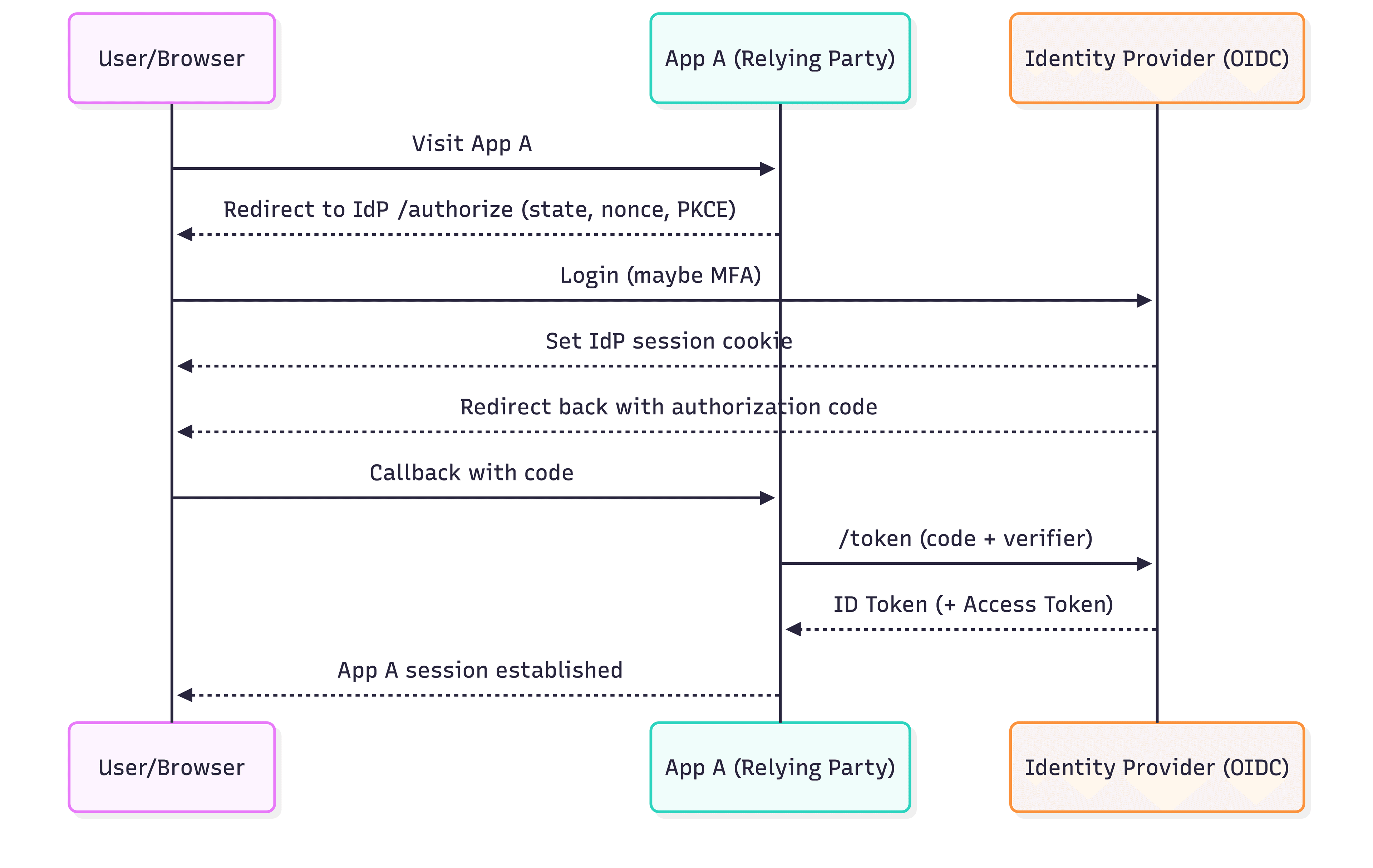

2.10 SSO & Federation: where it fits and how it works

SSO (Single Sign-On) is primarily an authentication concept:

“I logged in once, and I can access multiple apps without re-entering credentials.”

Under the hood, it’s usually implemented via OIDC (modern) or SAML (enterprise classic).

The key mental model: IdP session vs App session

IdP session: the Identity Provider remembers the user is authenticated (typically via an IdP cookie).

App session: each app still usually creates its own local session (its own cookie/session).

SSO means: the next app can redirect to the IdP and get back a successful result without showing a login prompt, because the IdP session already exists.

OIDC-style SSO

Why SLO (Single Logout) is harder than SSO

“Logout everywhere” is messy because:

multiple apps have independent sessions

users have multiple devices/browsers

IdP logout doesn’t always reliably propagate

Many teams accept:

“logout this app” + short TTL + step-up MFA for sensitive operations, rather than perfect global logout.

3) Authorization deep dive

Authentication answers “who are you?”. Authorization answers “what are you allowed to do, to which resource, under which conditions?” OWASP keeps emphasizing that most real incidents are authorization failures, and that access control is only effective when enforced in trusted server-side code (not in the UI).

3.1 The authorization vocabulary you’ll actually use

A clean, practical mapping:

Permission: an atomic capability, e.g. invoice:read, invoice:refund.

Scope (OAuth): a string representing requested/issued permissions for an access token; semantics are deployment-defined.

Role (RBAC): a named bundle of permissions, e.g. finance_admin.

Attributes (ABAC): properties of subject/object/action/environment (e.g. user.department, invoice.amount, ip_risk).

Relationship (ReBAC): a relation between a subject and an object, e.g. “Alice is viewer of Doc-123” (sharing-style systems).

Claims: data carried in credentials (JWT claims like sub, aud, scope, roles), used as inputs to authorization.

3.2 Golden rules

These are boring, but they’re the reason your app doesn’t end up in an incident report:

Deny by default. Allow only what you explicitly permit.

Enforce on the server (API/boundary). UI checks are not security.

Check both “action” and “data”.

Function-level: “can this user call POST /refund?”

Object-level: “can this user refund this invoice?” (ownership/tenant/relationship)

Don’t trust client-provided authorization metadata. Never trust role=admin in the request body, and be careful even with path params like /tenant/{tenantId}.

Make multi-tenant boundaries unbreakable. Tenant isolation should be a hard invariant enforced by the API and datastore queries.

3.3 Scopes (OAuth): good for coarse-grained API permissions

OAuth defines scope as a mechanism for limited access; the exact meaning of scope strings is left to deployments.

When scopes shine

“This token can call these API operations”:

read:profile,invoice:writeUser consent screens (“This app requests access to…”)

Common scope pitfalls

Overbroad scopes (blast radius)

Using scopes to model complex resource sharing (scopes don’t express “only this document” well)

Treating scopes as organizational roles (can work, but usually becomes messy)

Typical middleware check

function requireScope(scope: string) {

return (req, res, next) => {

const scopes = (req.user?.scope ?? "").split(" ");

if (!scopes.includes(scope)) return res.status(403).send("Forbidden");

next();

};

}3.3 RBAC: roles bundle permissions

RBAC is standardized/defined in the NIST RBAC model work and related guidance.

When RBAC shines

Internal tools, admin consoles

Stable “job function” permissions

“Most users fit into a small set of roles”

Where RBAC breaks down

Per-resource sharing (Doc A viewer, Doc B editor)

“Role explosion” in multi-tenant SaaS if every tenant wants custom roles

Production RBAC practice

Keep roles tenant-scoped: tenant_admin, tenant_member

Map roles → permissions in a single place (avoid duplicated logic)

Add constraints when needed (e.g., separation of duties) — RBAC literature covers constrained variants.

3.4 ABAC: policies over attributes

NIST defines ABAC decisions as evaluations over subject, object, action, and environment attributes.

Example policy (human-readable)

Allow

refund:createif:user.department == "finance"ANDinvoice.amount < 1000ANDdevice_risk == "low"

Pros

Fine-grained control without role explosion

Easy to add “context” (time, IP risk, MFA state)

Cons

You need a disciplined attribute model (source of truth, freshness, audit)

Policy debugging becomes its own engineering task

NIST’s ABAC guide also discusses reference architectures that include concepts like PDP/PEP (decision vs enforcement).

3.5 ReBAC: relationship-based access (sharing systems)

If your product looks like:

“Share this doc with Alice as viewer”

“Teams, folders, projects, ownership, membership”

…you are naturally in ReBAC territory.

Zanzibar (Google) is a well-known, large-scale authorization system for relationship/ACL-style permissions.

Mental model

Store tuples like: “user U is viewer/editor/owner of object O”

Authorization check becomes: “does relationship path exist?”

This model is excellent for “who can access this object?” at scale.

3.6 PDP/PEP: consistent decisions, local enforcement

A practical way to stop authorization logic from fragmenting across services:

PEP (Policy Enforcement Point): your gateway/service middleware that asks “allow or deny?”

PDP (Policy Decision Point): a centralized policy evaluator

Open Policy Agent (OPA) explicitly frames itself as a PDP and describes applications as PEPs.

Why teams adopt PDP/PEP

One policy language / one place to review changes

Better auditability

Less “if role == …” copy-paste

(You can run PDP as a sidecar, a central service, or embedded library—OPA docs cover deployment options.)

3.7 Multi-tenant authorization: the “don’t leak” invariant

Most SaaS data leaks are boring:

An API forgets to filter by tenant_id

Or trusts a user-supplied tenant id

Hard rule

Derive tenant_id from trusted identity (claims/session), not from request input.

Apply it to every query, not as an afterthought.

Pattern: tenant guard + query scoping (pseudo)

def require_tenant(claims):

tenant_id = claims["tenant_id"] # trusted claim

return tenant_id

# later in handler:

tenant_id = require_tenant(claims)

rows = db.query(Invoices).filter_by(tenant_id=tenant_id).all()Pair this with “deny by default” and server-side enforcement guidance from OWASP

3.8 Testing + auditing: authorization must be observable

Authorization bugs survive because they’re not tested like business logic.

Minimum bar

Unit tests for policy decisions (“allow/deny matrix”)

Integration tests at the API boundary (object-level access)

Audit logs for sensitive decisions (admin actions, role changes, money movement)

OWASP’s Authorization Cheat Sheet is a solid checklist for building maintainable, robust authorization logic.

4) Auth0 (and similar providers) in real projects

Auth0 isn’t “just login UI”. In production it typically plays multiple roles at once:

OIDC Provider / Identity Provider (IdP): authenticates the user (password, social, enterprise federation) and returns an OIDC identity result.

OAuth 2.0 Authorization Server: issues access tokens (and optionally refresh tokens) that APIs can accept.

Configuration + policy surface: where you define apps, APIs, permissions, RBAC toggles, token contents, and extensibility hooks.

B2B multi-tenant features(optional): Organizations and related architecture patterns.

The key to integrating Auth0 cleanly is to map its objects to your architecture boundaries.

4.1 Auth0’s building blocks (what they mean in system design)

Tenant

A tenant is your top-level configuration and security boundary (domain, keys, connections, branding, etc.). In most teams: one product environment = one tenant (dev/staging/prod).

Application (OAuth Client)

Represents “who is requesting login” (e.g., your Next.js web app, your mobile app). Each app has client settings and allowed callback/logout URLs.

API (Resource Server)

Represents “who will accept access tokens” (your FastAPI, your microservices behind a gateway). You give the API an Identifier, which is used as the audience when requesting an access token for that API.

Permissions / Scopes

On an Auth0 API, you define permissions (often used as OAuth scopes) that can later appear in tokens and be enforced by your backend.

Actions (Extensibility)

Actions are Auth0’s modern “run custom code in the auth pipeline” mechanism (post-login, etc.). The Actions API lets you:

set custom claims in tokens

add/remove scopes

implement custom checks / enrichment

Auth0 also publishes the end-of-life timeline for the older extensibility mechanisms (Rules/Hooks), which affects how you should design new integrations.

Organizations (B2B)

If you’re building B2B SaaS where customers are “companies/tenants”, Auth0 Organizations is a first-class feature designed for that. Auth0 publishes both best practices and “multiple organization architecture” guidance for these designs.

4.2 How Auth0 supports Authorization in practice

Auth0 gives you two layers you’ll commonly combine:

Layer A: API permissions (OAuth scopes)

Define permissions on the API (e.g., read:profile, invoice:refund) and enforce them in your backend.

Layer B: RBAC for APIs (roles → permissions)

Auth0 lets you enable RBAC for a given API in the dashboard, and optionally include permissions in the access token.A practical mapping to Part 3:

Scopes/permissions: the thing your API checks on each request.

Roles: a management convenience that assigns a set of permissions to users.

4.3 Custom claims: where you add tenant_id, org_id, feature flags, etc.

This is the glue between “identity” and “authorization inputs”.In an Auth0 Action (post-login), you can set custom claims on the access token via api.accessToken.setCustomClaim(name, value). Auth0 explicitly notes the claim name may need to be a fully-qualified URL (namespaced).Example: add tenant_idand org_id(namespaced):

/**

* Post-login Action

*/

exports.onExecutePostLogin = async (event, api) => {

const ns = "https://theaispace.xyz/claims";

// Example sources:

// - event.organization.id (if using Auth0 Organizations)

// - event.user.app_metadata / user_metadata

const tenantId = event.user.app_metadata?.tenant_id;

const orgId = event.organization?.id;

if (tenantId) api.accessToken.setCustomClaim(`${ns}/tenant_id`, tenantId);

if (orgId) api.accessToken.setCustomClaim(`${ns}/org_id`, orgId);

};Why namespacing matters: Auth0 recommends a namespaced format to avoid collisions with reserved or future claims.

4.4 Organizations: Auth0’s B2B multi-tenant lane

If your product is licensed to other businesses and you need:

per-customer branding (lightweight)

per-customer federation requirements

customer-scoped membership and invitation flows

Auth0 Organizations is presented as an “ideal solution for most multi-tenant use cases” in their best-practices doc, and the Organizations overview positions it specifically for B2B implementations.Auth0 also provides a “Multiple Organization Architecture” guide describing design choices like whether users are shared across organizations or isolated to one.Practical app-side pattern:

Use Organization for who the customer is

Use your app DB for what the customer can see/do (RBAC/ABAC/ReBAC), but pass

org_id/tenant_idas a trusted claim into your authorization layer.

4.5 Refresh tokens + rotation: what Auth0 gives you out of the box

Auth0 documents:

what refresh tokens are and how they’re used

“deny list” behavior

offline access switch

refresh token rotation as a hardening measure

In practice:

Access tokens stay short-lived.

Refresh token rotation reduces the risk of a stolen refresh token being replayed.

You configure rotation in the dashboard (including overlap period).

5) Threat model: what breaks real auth systems

If Section 2–4 are the happy path, this section is the map of how attackers actually win.OWASP’s Top 10 is a good reality check: authentication failures, broken access control, security misconfiguration, and logging/monitoring gaps show up repeatedly as dominant risk categories.

5.1 Credential attacks: credential stuffing, password spraying, brute force

What it looks like

Attackers try passwords leaked from other sites (“credential stuffing”) or try a few common passwords across many accounts (“password spraying”).

You’ll often see this show up in OWASP’s “Identification and Authentication Failures” category.

Mitigations that actually matter

MFA: OWASP’s MFA guidance frames it as a major defense against password-based attacks.

Rate limiting + progressive delays (per IP, per account, per device fingerprint).

Bot defenses for login and password reset (CAPTCHA or risk-based checks).

Disable account enumeration: login/reset responses should not reveal whether a user exists.

Password hashing: use strong adaptive password hashing (OWASP password storage guidance favors modern schemes; bcrypt is for legacy contexts when others aren’t available).

Interview tip

“Credential stuffing is the default attack. MFA + rate limiting + good password hashing + non-enumerating auth endpoints are the baseline.”

5.2 Session & cookie threats: fixation, hijacking, and cookie misconfiguration

Session fixation

Attack: the attacker forces the victim to use a session ID the attacker already knows; if the server doesn’t rotate it after login, the attacker hijacks the authenticated session.

Fix

Rotate session ID on login and on privilege elevation (e.g., after MFA).

Don’t accept session IDs from URLs; OWASP explicitly calls out “exposes session identifier in the URL” as an auth failure pattern.

Session hijacking via cookie theft/leak

Fix baseline

Set cookies with

HttpOnly; Secure; SameSite=Lax/Strict.Consider cookie prefixes (

__Host-,__Secure-) as additional hardening (supported in modern cookie specs).

Set-Cookie: app_session=...; Path=/; HttpOnly; Secure; SameSite=Lax

5.3 CSRF: cookies auto-send, attackers abuse that

Threat: a malicious site tricks a logged-in user’s browser into sending a state-changing request to your site, and the cookie goes along for the ride.

Core defenses

CSRF tokens on all state-changing requests (POST/PUT/PATCH/DELETE).

Origin/Referer validation (defense-in-depth; especially for “high value” operations).

SameSite cookies reduce CSRF in many cases, but treat as defense-in-depth, not the only control.

Practical pattern (double submit / header token)

// client sends:

fetch("/api/transfer", {

method: "POST",

headers: { "X-CSRF-Token": csrfToken },

body: JSON.stringify(payload),

});

// server verifies X-CSRF-Token matches server-side or signed token expectation5.4 XSS: the “authorization bypass machine” (steal sessions, perform actions)

OWASP’s XSS guidance is blunt: XSS can lead to account impersonation, data theft, and arbitrary actions as the user.

Auth-specific impact

If your auth credential is accessible to JS (tokens in storage), XSS can exfiltrate it.

Even if cookies are HttpOnly, XSS can still perform actions as the user (“session riding”)—it just can’t read the cookie value.

Mitigations

Output encoding + input validation (your primary fix).

CSP (Content Security Policy) as defense-in-depth; OWASP highlights CSP’s value specifically against XSS exploitation.

Keep tokens out of JS when possible (BFF/SSR helps)

Example CSP starter (tune to your app; don’t cargo-cult):

Content-Security-Policy: default-src 'self'; script-src 'self'; object-src 'none'; base-uri 'self'

5.5 OAuth/OIDC flow threats: redirect attacks, missing state/nonce, code interception

OAuth is safe only when you implement the “boring details”. OAuth 2.0 security best current practice (BCP) exists because real systems repeatedly got these wrong.

Redirect URI abuse / open redirects

If redirect URIs are loosely validated, attackers can steal authorization codes or tokens.

OWASP has a dedicated cheat sheet for unvalidated redirects, and OAuth guidance repeatedly stresses strict redirect handling.

Rule: redirect URI allowlist + exact match (no wildcards unless you fully understand the consequences).

Missing state (CSRF) and missing nonce (OIDC replay)

statebinds the auth response to the initiating browser session (anti-CSRF).noncebinds the ID token to the login request and mitigates replay; OIDC says clients must verifynoncewhen present.

Code interception (public clients)

Use Authorization Code + PKCE for SPAs/mobile; PKCE is the standard defense for intercepted authorization codes.

Native app embedded web views

For native apps, best current practice is to use an external user-agent (system browser).

5.6 Bearer token replay + leakage (the “logs, headers, storage” problem)

Bearer tokens have a core property: whoever has the token can use it—that’s literally the definition in RFC 6750.So the game becomes: don’t let tokens leak and make leaked tokens short-lived / hard to replay.

Common leak paths

Tokens accidentally written to logs (reverse proxies, client logs).

Tokens stored in browser storage and stolen via XSS.

Tokens exposed through overly-permissive CORS + credentialed endpoints.

OWASP testing guidance calls out dangerous patterns like

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *or blindly reflecting origins.

Mitigations

Short access-token TTL + least privilege.

Avoid putting tokens in URLs (they leak via referrers/history/logs).

If you must store tokens in the browser, Auth0 recommends in-memory storage and notes Web Workers can help isolate token handling.

For higher-security needs: sender-constrained tokens like DPoP can help detect replay attacks.

5.7 Refresh token theft: rotation + reuse detection (and concurrency pitfalls)

Refresh tokens are high-value because they can mint new access tokens. Auth0 recommends rotation and reuse detection as mitigations.

What to implement

Refresh token rotation

Automatic reuse detection

Overlap / leeway window to prevent false positives under concurrency (Auth0 documents a “Rotation Overlap Period” precisely for this).

5.8 JWKS/key rotation failures: “everything is down” incidents

If your API validates JWTs via JWKS and you cache keys incorrectly, you can get:

sudden spikes of 401s when keys rotate

or worse, accepting tokens you shouldn’t if you validate incorrectly

Good practice

Discover the

jwks_urivia metadata and cache responsibly.Cache with TTL, but also refresh on unknown

kid(key rotation).

5.9 Clickjacking: “UI tricks that cause real transactions”

Clickjacking frames your site and tricks users into clicking hidden UI controls. OWASP and MDN both recommend using X-Frame-Optionsand/or CSP frame-ancestors.

X-Frame-Options: DENY

Content-Security-Policy: frame-ancestors 'none';5.10 Logging & monitoring: you can’t defend what you can’t see

OWASP explicitly calls out that without logging and monitoring, breaches often can’t be detected. It also lists authentication events (logins, failed logins, high-value transactions) as examples of auditable events that should be logged.

Minimum set to log

login success/failure (+ reason class, not raw secrets)

MFA challenge events (enroll, pass, fail)

refresh token reuse detection triggers

role/permission changes

“high value” actions (refunds, payouts, org membership changes)

Alerting

spikes in failed logins per account / per IP

unusual geo/IP/device changes

repeated 403s on sensitive endpoints (possible authz probing)

References

OAuth 2.0 Authorization Framework (RFC 6749):https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc6749

OAuth 2.0 Bearer Token Usage (RFC 6750):https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc6750

Proof Key for Code Exchange (PKCE) (RFC 7636):https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc7636

OAuth 2.0 for Native Apps (BCP) (RFC 8252):https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc8252

OAuth 2.0 Token Revocation (RFC 7009):https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc7009

JSON Web Token (JWT) (RFC 7519):https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc7519

OAuth 2.0 Security Best Current Practice (RFC 9700):https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc9700

OpenID Connect Core 1.0:https://openid.net/specs/openid-connect-core-1_0.html

OpenID Connect Discovery 1.0:https://openid.net/specs/openid-connect-discovery-1_0.html

DPoP (RFC 9449):https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc9449

OAuth 2.0 mTLS-bound access tokens (RFC 8705):https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc8705

OWASP Top 10 (2025):https://owasp.org/Top10/2025/

NIST RBAC project:https://csrc.nist.gov/projects/role-based-access-control

nextjs-auth0 SDK docs:https://auth0.github.io/nextjs-auth0/

Auth0Client server API:https://auth0.github.io/nextjs-auth0/classes/server.Auth0Client.html

Access tokens:https://auth0.com/docs/secure/tokens/access-tokens

Get access tokens / audience:https://auth0.com/docs/secure/tokens/access-tokens/get-access-tokens

Add API permissions:https://auth0.com/docs/get-started/apis/add-api-permissions

Enable RBAC for APIs:https://auth0.com/docs/get-started/apis/enable-role-based-access-control-for-apis

Custom claims:https://auth0.com/docs/secure/tokens/json-web-tokens/create-custom-claims

Post-login Action API object:https://auth0.com/docs/customize/actions/explore-triggers/signup-and-login-triggers/login-trigger/post-login-api-object

Token storage guidance:https://auth0.com/docs/secure/security-guidance/data-security/token-storage

Refresh tokens:https://auth0.com/docs/secure/tokens/refresh-tokens

Refresh token rotation:https://auth0.com/docs/secure/tokens/refresh-tokens/refresh-token-rotation

Configure refresh token rotation:https://auth0.com/docs/secure/tokens/refresh-tokens/configure-refresh-token-rotation

MRRT:https://auth0.com/docs/secure/tokens/refresh-tokens/multi-resource-refresh-token

Organizations overview:https://auth0.com/docs/manage-users/organizations/organizations-overview

Multi-tenant best practices:https://auth0.com/docs/get-started/auth0-overview/create-tenants/multi-tenant-apps-best-practices

Multiple organization architecture:https://auth0.com/docs/get-started/architecture-scenarios/multiple-organization-architecture

Rules (legacy) + EOL notes:https://auth0.com/docs/customize/rules

Rules/Hooks EOL blog:https://auth0.com/blog/preparing-for-rules-and-hooks-end-of-life/

Zanzibar paper (Google, USENIX ATC’19):https://www.usenix.org/conference/atc19/presentation/pang