An engineer’s “reverse tour” of the browser pipeline .

30-second interview answer

In Chrome, the critical rendering path is: parse HTML into the DOM, parse CSS and compute computed styles, run layout (in modern Chrome, LayoutNG) to produce geometry (fragments), run pre-paint to build property trees (transform/clip/effect/scroll) and paint chunks, then paint records a display list (draw commands, not pixels). After commit, the compositor (

cc) performs layerization (CompositeAfterPaint), tiles content, rasterizes tiles (via Skia/GPU) into textures, and submits a CompositorFrame to Viz, which aggregates and presents pixels to the screen. In practice, I use this model to debug jank: figure out whether the bottleneck is JS main-thread, style/layout, paint/raster, or compositing, and then verify with DevTools (Performance + Rendering tools).

One-liner version: DOM → Style → LayoutNG → Pre-paint (property trees/paint chunks) → Paint (display list) → Commit → CAP → Tiling → Raster → Viz → Pixels.

Who does what? Processes and threads (the cast)

Chrome is multi-process for stability and security:

Browser process (the manager)

Owns:

The “chrome” UI (tabs, address bar, menus)

Most privileged I/O (disk, device access)

Coordinates navigation and network loading (exact details vary, but treat it as the orchestrator)

Renderer process (the sandbox)

Owns page execution:

Blink (rendering engine: HTML/CSS, style, layout, paint recording)

V8 (JavaScript engine) A typical tab/site instance runs in its own renderer process for isolation.

Viz + GPU (the final compositor and presenter)

Viz (“visuals”) is the compositing/presentation service that aggregates frames and works with the GPU to present pixels.

The GPU process (and platform graphics stack) helps rasterize and present the final frame.

Inside the renderer process, two threads matter most:

Main thread: HTML parsing, style calculation, layout, and paint recording (and also runs JS).

Compositor thread (Chromium’s compositor subsystem, often called

cc): builds frames, handles scrolling and many animations off the main thread, manages tiling priorities, and submits compositor frames to Viz.

Practical takeaway: if you block the main thread (long JS tasks), you can still sometimes scroll/animate smoothly if the work is “compositor-friendly” — but only up to a point.

A modern “life of a frame”: the pipeline at 10,000 feet

Here’s the big picture:

Parse: HTML bytes → DOM

Style: CSS rules + DOM → computed styles

Layout (LayoutNG): computed styles → geometry → immutable fragment tree

Pre-paint: build property trees + paint chunks

Paint (recording): produce a display list / paint artifacts (instructions, not pixels)

Commit: hand results to the compositor thread (

cc)Layerization + Compositing(CompositeAfterPaint / CAP): decide composited structure after paint

Tiling: split content into tiles, prioritize visible tiles

Raster: tiles’ paint instructions → pixel textures (often GPU accelerated via Skia)

Submit → Aggregate → Present: compositor frame → Viz → screen

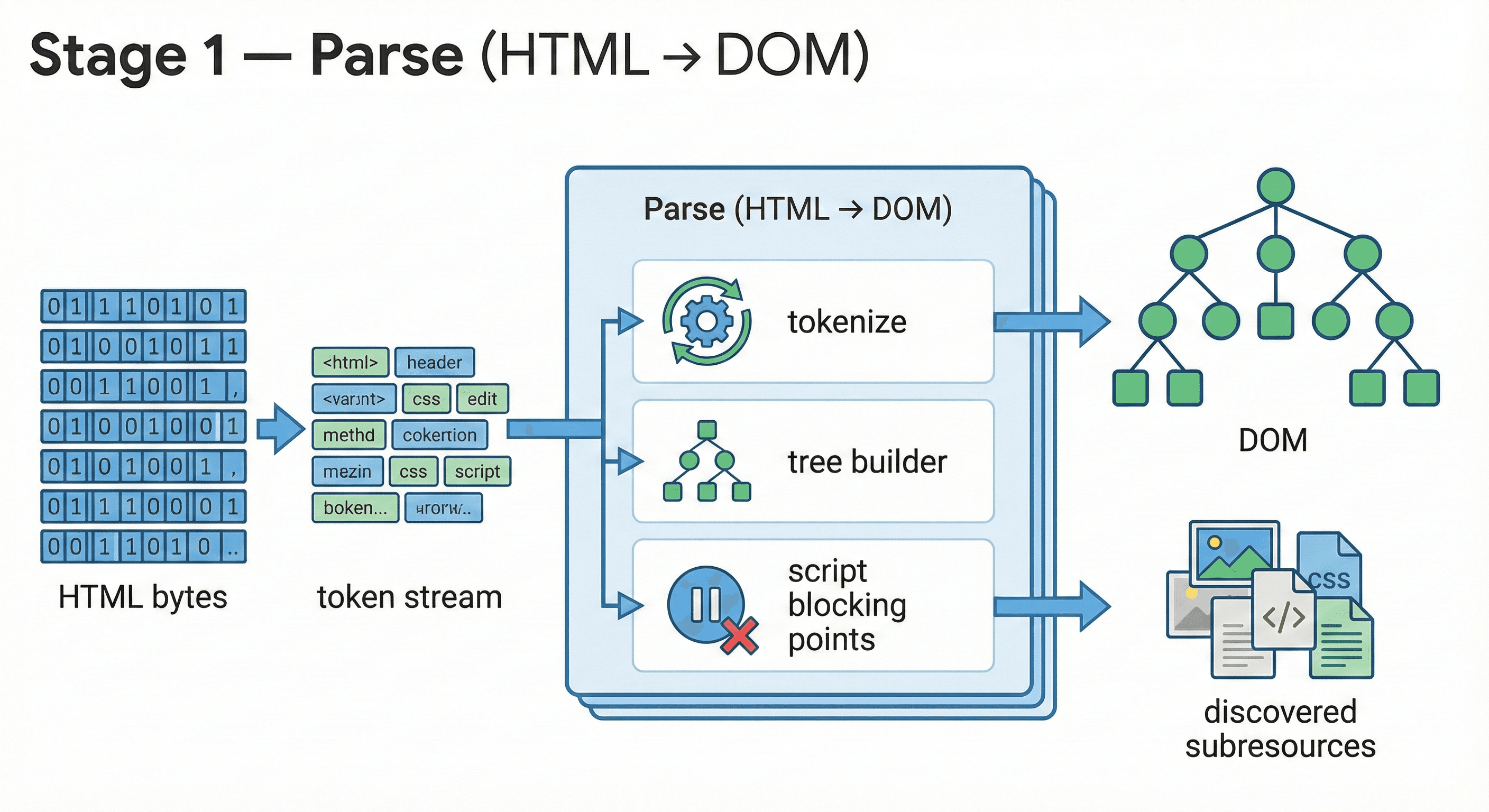

1) HTML parsing → DOM tree

Input: HTML bytes from the network (or cache), plus parser state.

What happens:

Chrome tokenizes HTML and builds nodes according to the HTML parsing algorithm.

During loading, some parsing work can be scheduled efficiently, but DOM mutations via JS (e.g.

innerHTML) can force synchronous main-thread work.

Output:

DOM tree

A set of “things to fetch”: CSS, JS, images, fonts…

Gotcha (important for performance): When the parser encounters a blocking <script>(without defer/async), HTML parsing pauses so JS can run — because that JS might mutate the DOM being constructed.

Parse

“HTML bytes” means the document arrives as a byte stream (network/cache); it’s decoded into characters (charset, usually UTF-8) before parsing.

A “token stream” is produced by the HTML tokenizer (StartTag/EndTag/Text tokens), which the tree builder consumes to construct the DOM.

“Script blocking points” refers to pauses in parsing for certain

<script>tags (fetch/execute) because scripts may mutate the DOM or affect parsing.Besides the DOM, parsing also discovers subresources to fetch (CSS, JS, images, fonts).

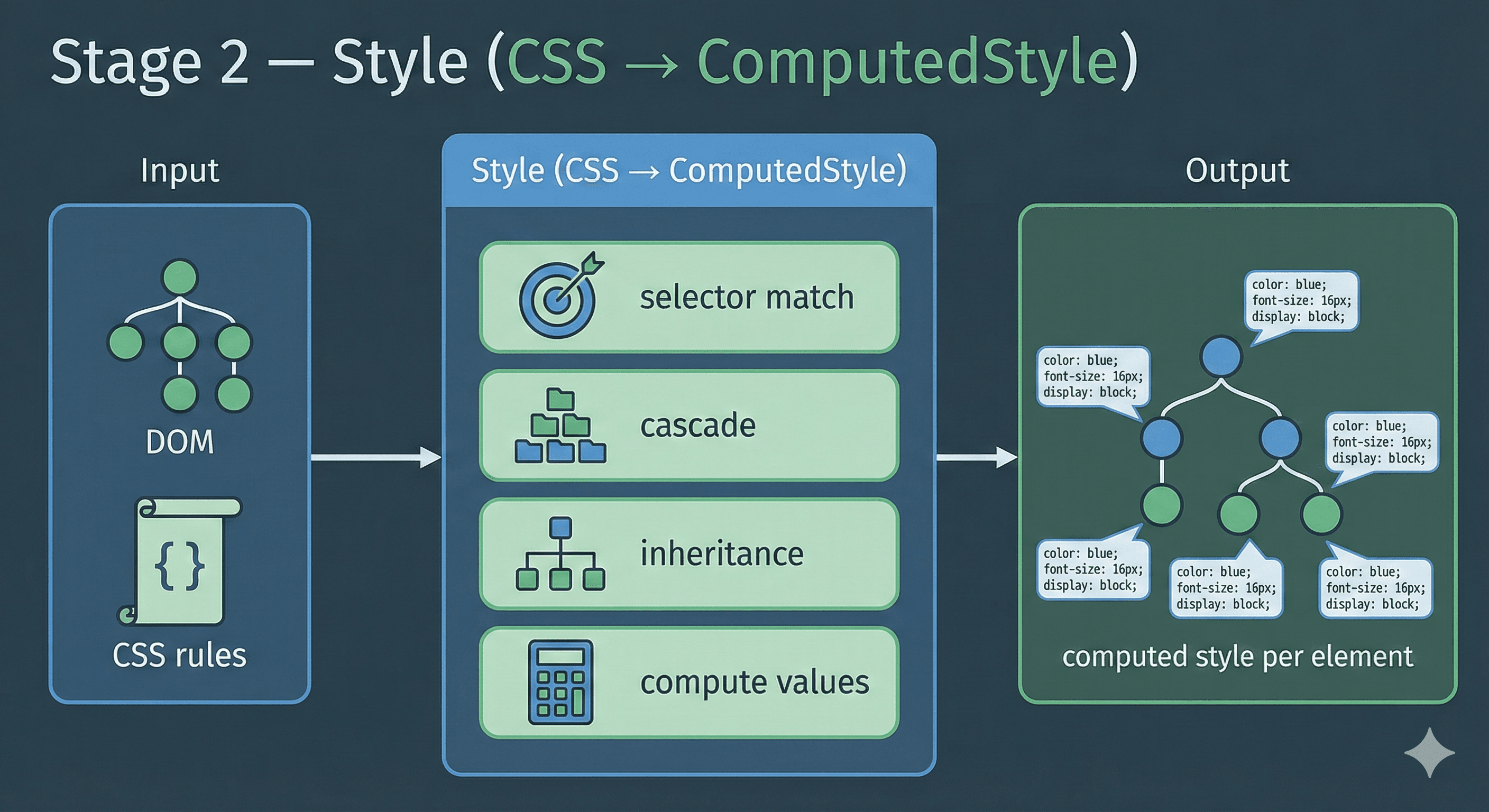

2) CSS parsing + Style calculation → ComputedStyle

Input:

DOM tree

CSS sources:

external stylesheets (

<link rel="stylesheet">)<style>blocksinline styles (

style="")user agent (UA) default styles

What happens:

CSS text is parsed into internal rule structures (often explained as “CSSOM”).

Selector matching + cascade + inheritance resolve the winning rules.

Abstract values become computed values (e.g.,

em→ px).

Output:

Per-element computed style (the exact values layout and paint need).

Engineering note: Not every DOM change triggers full style recalculation; Chrome uses invalidation to limit recalculation scope.

Style

CSS rules come from multiple sources: UA defaults, external stylesheets,

<style>blocks, and inline styles.Selector matching determines which rules apply; the cascade resolves conflicts (origin/order/specificity).

Inheritance propagates certain properties from parent to child; “compute values” resolves units into usable computed values.

The output is computed style per element, which feeds layout and paint.

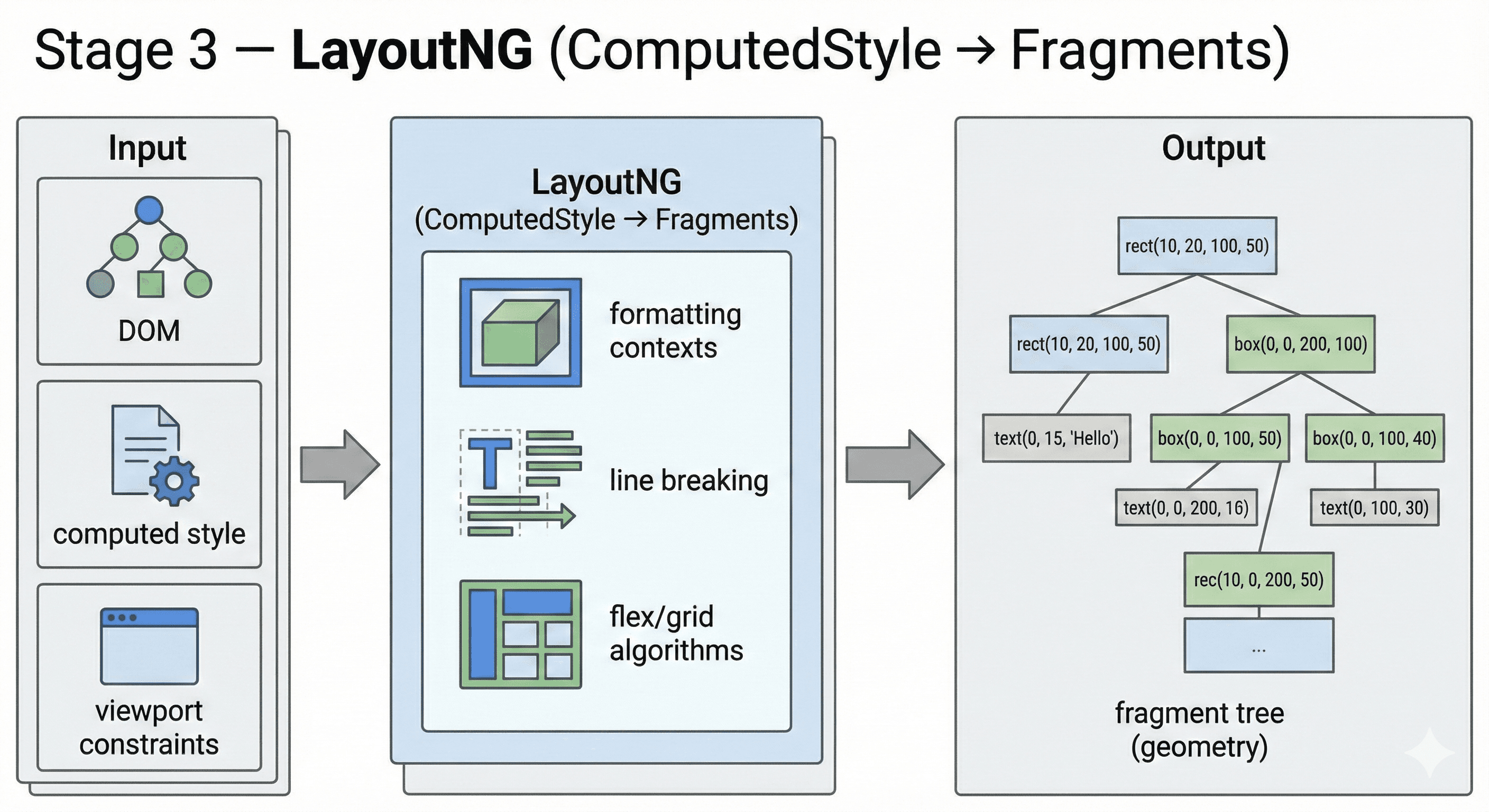

3) Layout (LayoutNG): compute geometry → immutable fragment tree

This is one of the biggest “old vs modern” differences.

What LayoutNG means

LayoutNG = Layout Next Generation.

Input:

DOM + computed styles

viewport / constraints (block/inline/flex/grid/table algorithms depend on available space)

writing mode, fonts, etc.

What happens:

Determine which elements participate:

display: none→ no layout objectvisibility: hidden→ participates in layout (takes space) but not painted

Run layout algorithms to compute:

box sizes/positions

line breaks, inline formatting

flex/grid placement

floats, etc.

Output:

Fragment tree (immutable layout output)

Instead of mutating a single long-lived tree in place, LayoutNG produces new, immutable layout results (“fragments”).

This separation helps caching and makes incremental layout more predictable.

Why you should care:

If you ever see layout jank, the real question usually isn’t “what is layout?”—it’s: what change is triggering layout repeatedly, and can I update the UI in a way that avoids re-layout (e.g., animate transform/opacityinstead of width/height, and batch DOM reads before writes)?

LayoutNG

“NG” in LayoutNG stands for Next Generation; the output is layout geometry, not pixels.

Viewport constraints (available size, writing mode, fonts) shape line breaking, box sizing, and placement.

Formatting contexts and algorithms (block/inline, flex, grid, tables) determine how elements participate in layout.

The output is a fragment tree describing positions/sizes (geometry) for the next stages.

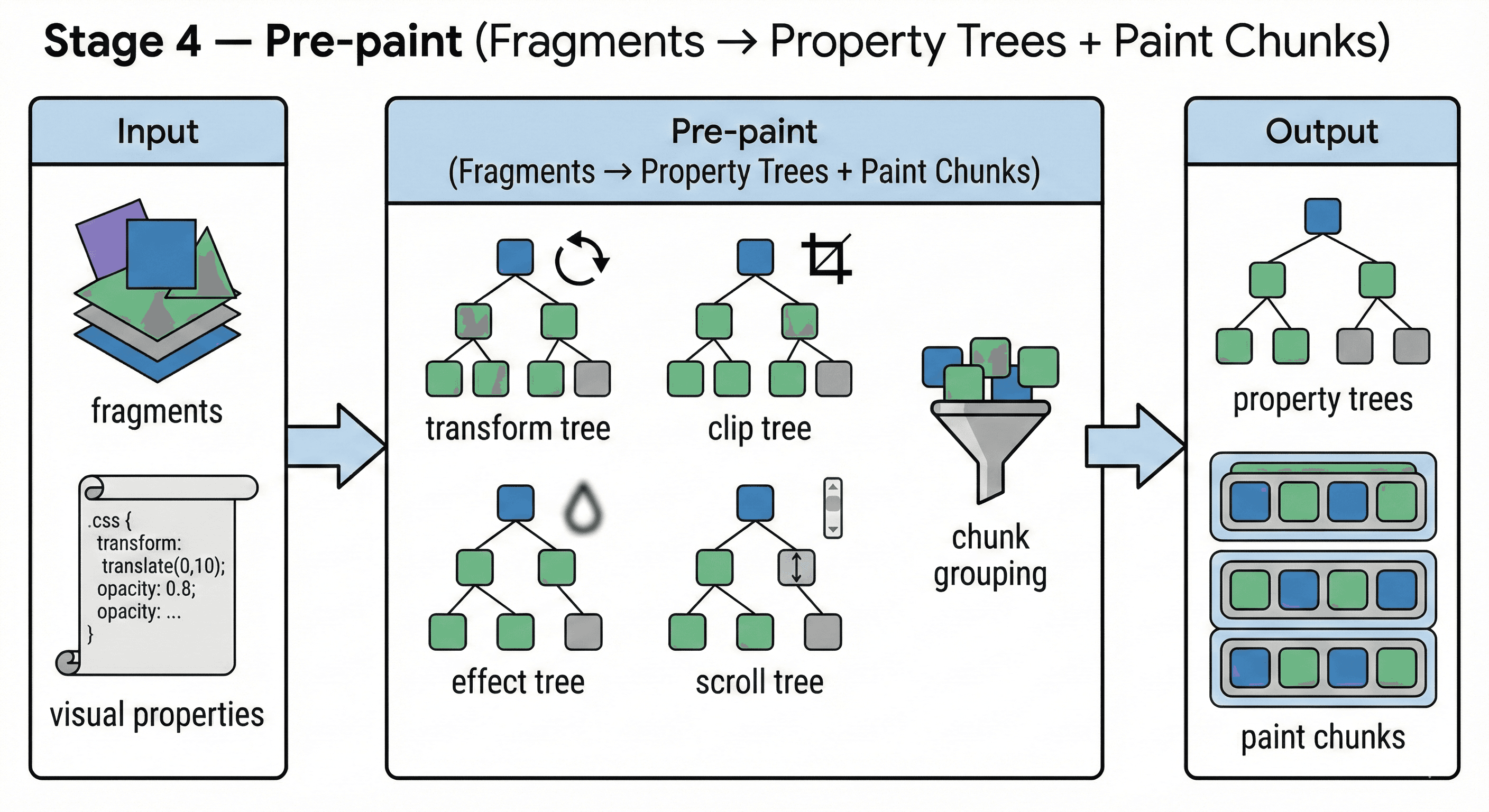

4) Pre-paint: property trees + paint chunks (bridge between layout and compositing)

Older “render pipeline” writeups often skip this stage, but it is central in RenderingNG.

Input:

Fragment tree (layout output)

Styles affecting transform/clip/effect/scroll and paint invalidation

What happens: Chrome builds property trees (a separate set of hierarchies that describe how visuals are transformed and clipped):

Transform tree: transforms (including scroll transforms)

Clip tree: overflow clips, clip-path, etc.

Effect tree: opacity, filters, blend modes, masks…

Scroll tree: scrolling relationships

It also groups painting output into paint chunks:

Adjacent display items with the same property-tree state are grouped.

These chunks become key inputs for layerization (what becomes composited) and invalidation.

Output:

Property trees + paint chunks

Why you should care: Property trees are a major reason compositor-side updates can be efficient: instead of recomputing everything, the compositor can update just the “interesting nodes”.

Pre-paint

Property trees model visual relationships separately: transform, clip, effect (opacity/filters), and scroll.

Paint chunks group adjacent draw items that share the same property-tree state, improving later layerization and invalidation.

This stage bridges “layout results” to “compositing-aware paint organization.”

The output (property trees + paint chunks) is used by paint recording and CAP layerization.

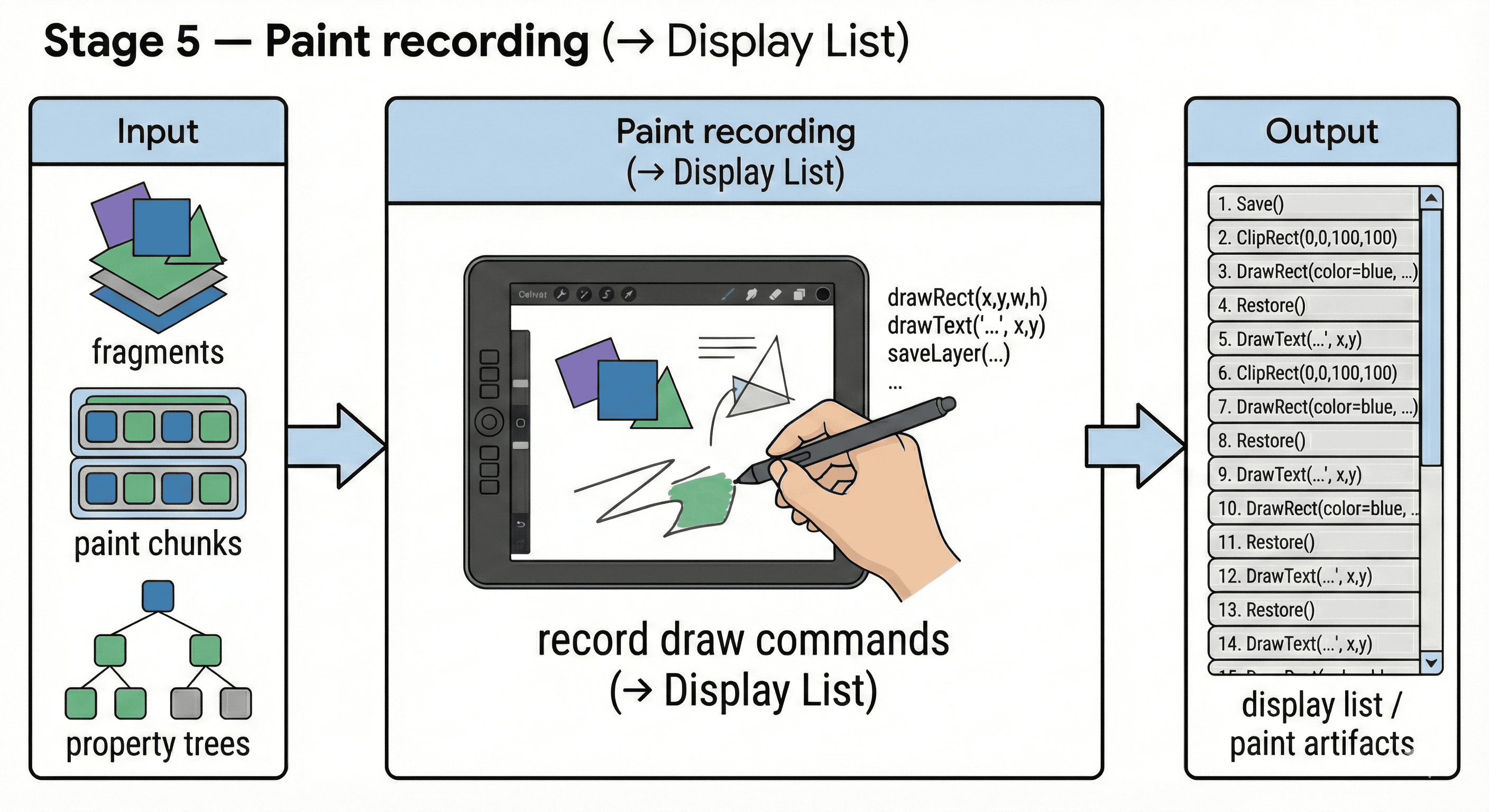

5) Paint (recording): create a display list (instructions, not pixels)

This is the most common source of confusion:

Paint recording ≠ Rasterization

Input:

Fragment tree + computed style

Property trees + paint chunks

What happens:

Blink records drawing commands into a display list (often via Skia picture/display items):

draw background rect

draw border

draw text glyphs

draw image

apply shadow, etc.

Output:

Display list / paint artifacts (the “instruction manual” for what to draw)

At this point, there are still no final pixels, only recorded commands.

Paint recording

Paint recording produces draw commands (a display list), not final pixels.

“Skia ops” are Skia’s drawing operations (e.g., drawRect/drawText/drawImage) recorded for replay.

The display list / paint artifacts can be replayed during rasterization to produce pixels for tiles.

Paint affects “what to draw”; rasterization affects “the cost to turn it into pixels.”

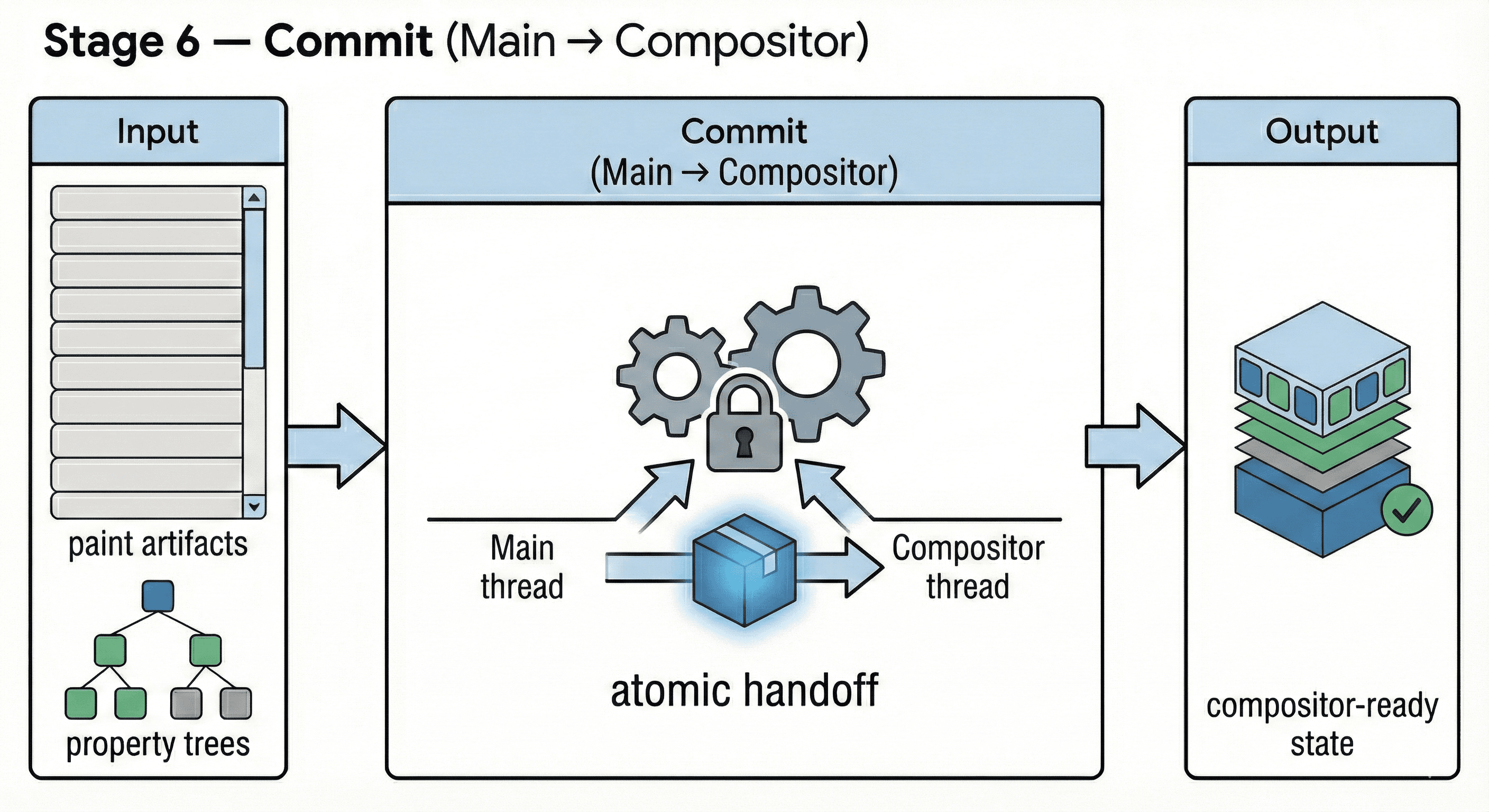

6) Commit: main thread hands off to the compositor thread (cc)

Once layout + paint artifacts are ready for a frame, the renderer performs a commit:

Main thread results are atomically handed to the compositor thread.

Main thread can go back to JS execution and handling events.

This handoff boundary is one reason “main thread busy” does not always mean “the screen can’t update at all”.

Commit

Commit is the boundary where main-thread results (paint artifacts + properties) are handed to the compositor thread.

“Atomic handoff” means the compositor sees a consistent snapshot of state for building the next frame.

This helps explain why some scrolling/animations can keep running even if the main thread is busy (within limits).

The output is compositor-ready state used for CAP/layerization and frame building.

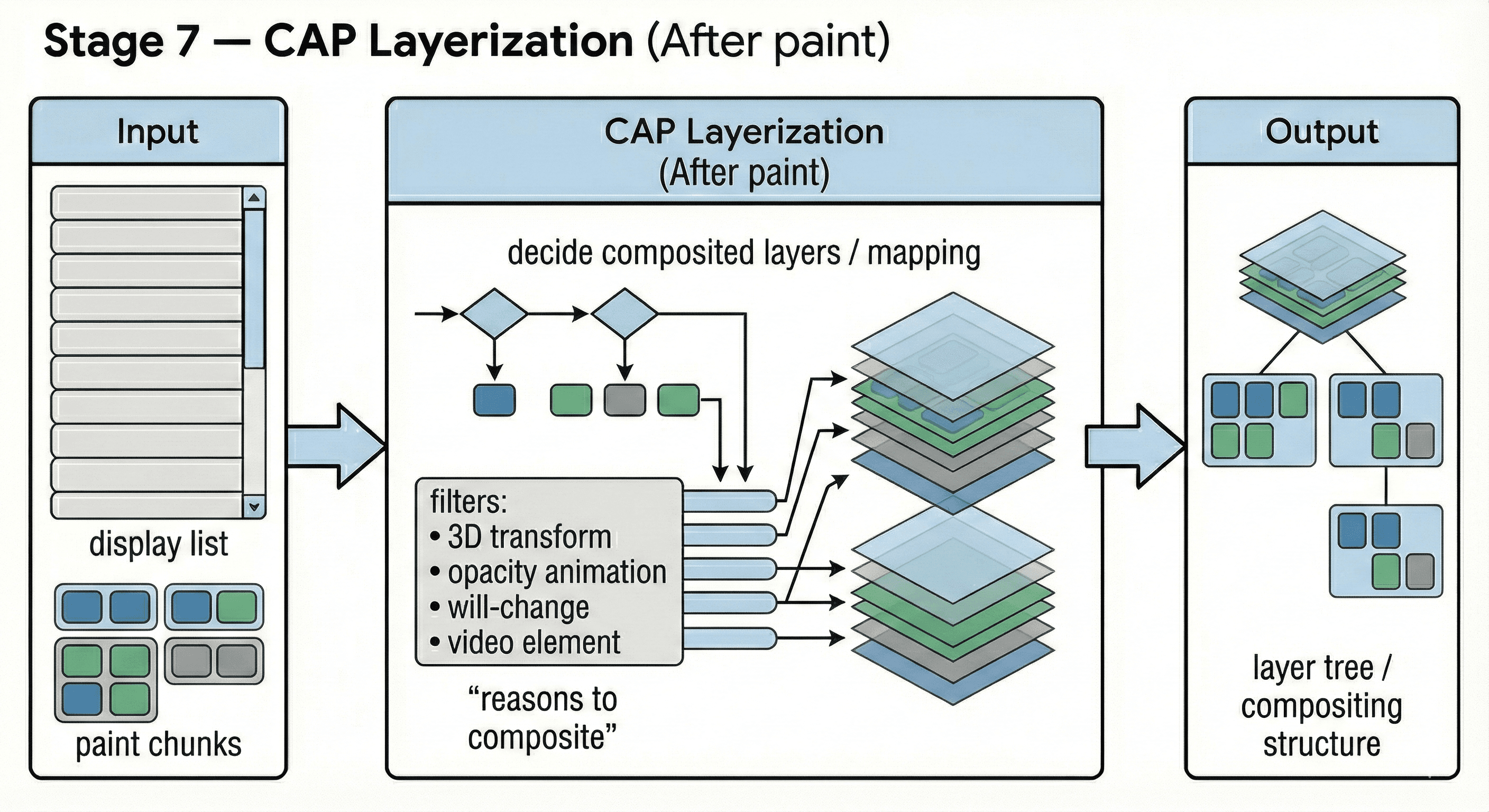

7) CompositeAfterPaint (CAP): layerization after paint

What CAP is (and why it matters)

CAP = Composite After Paint. Historically, Chrome decided compositing layers before paint, which was brittle. Under CAP, Chrome:

paints a global set of display items

then decides how to layerize and composite them

Layerization = deciding what content should be in its own composited layer (often backed by GPU textures), and how paint chunks map to compositor layers.

Input:

Display list + paint chunks

Property trees

“Reasons to composite” (animations, scrolling, effects,

will-change, etc.)

Output:

A compositor-side representation that can produce a CompositorFrame (RenderPasses + DrawQuads)

Practical takeaway:

“Stacking context” is a correctness concept (paint order).

“Composited layers” are an architecture/perf concept. They overlap sometimes, but they are not the same thing.

CAP Layerization (After paint)

CAP means Composite After Paint: paint first, then decide how to layerize and composite.

“Reasons to composite” include transform/opacity animations, filters, fixed/sticky behavior, and

will-change.This stage maps paint chunks into composited layers and determines the compositing structure.

The output strongly affects tiling/raster cost and how smooth animations/scrolling can be.

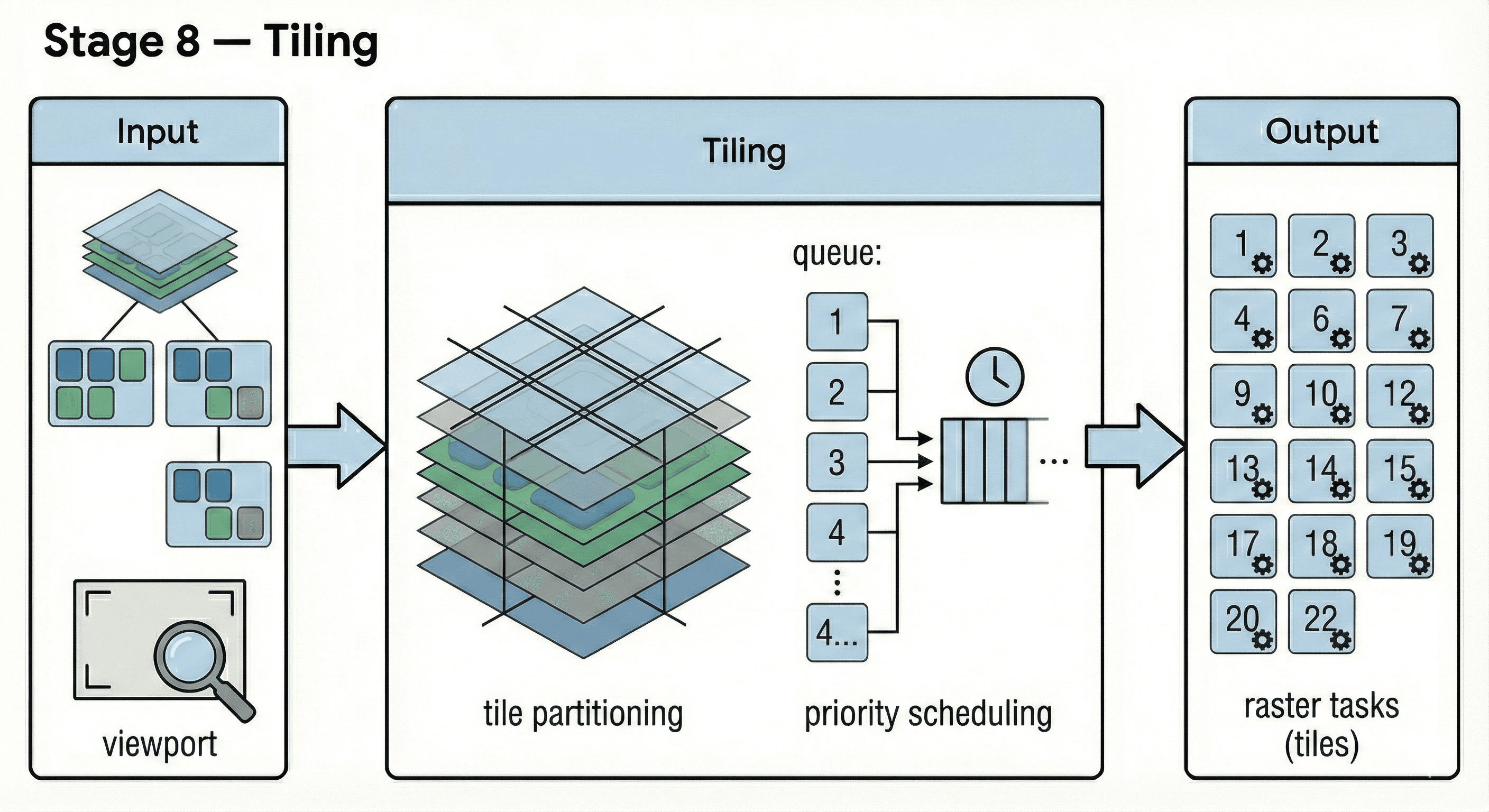

8) Tiling: split large content into tiles (and prioritize)

Pages can be huge. Chrome avoids rasterizing one giant bitmap.

Input:

composited layers + viewport info

What happens:

Split content into fixed-size tiles

Prioritize tiles near the viewport first

Schedule raster tasks for needed tiles

Output:

Raster tasks (per tile)

Tiling

Large surfaces are split into tiles so the browser rasterizes only what’s needed near the viewport.

Priority scheduling focuses on visible/soon-to-be-visible tiles first; offscreen tiles are deprioritized.

Tiling explains effects like “checkerboarding” (blank/low-res regions during fast scroll).

The output is a set of raster tasks per tile.

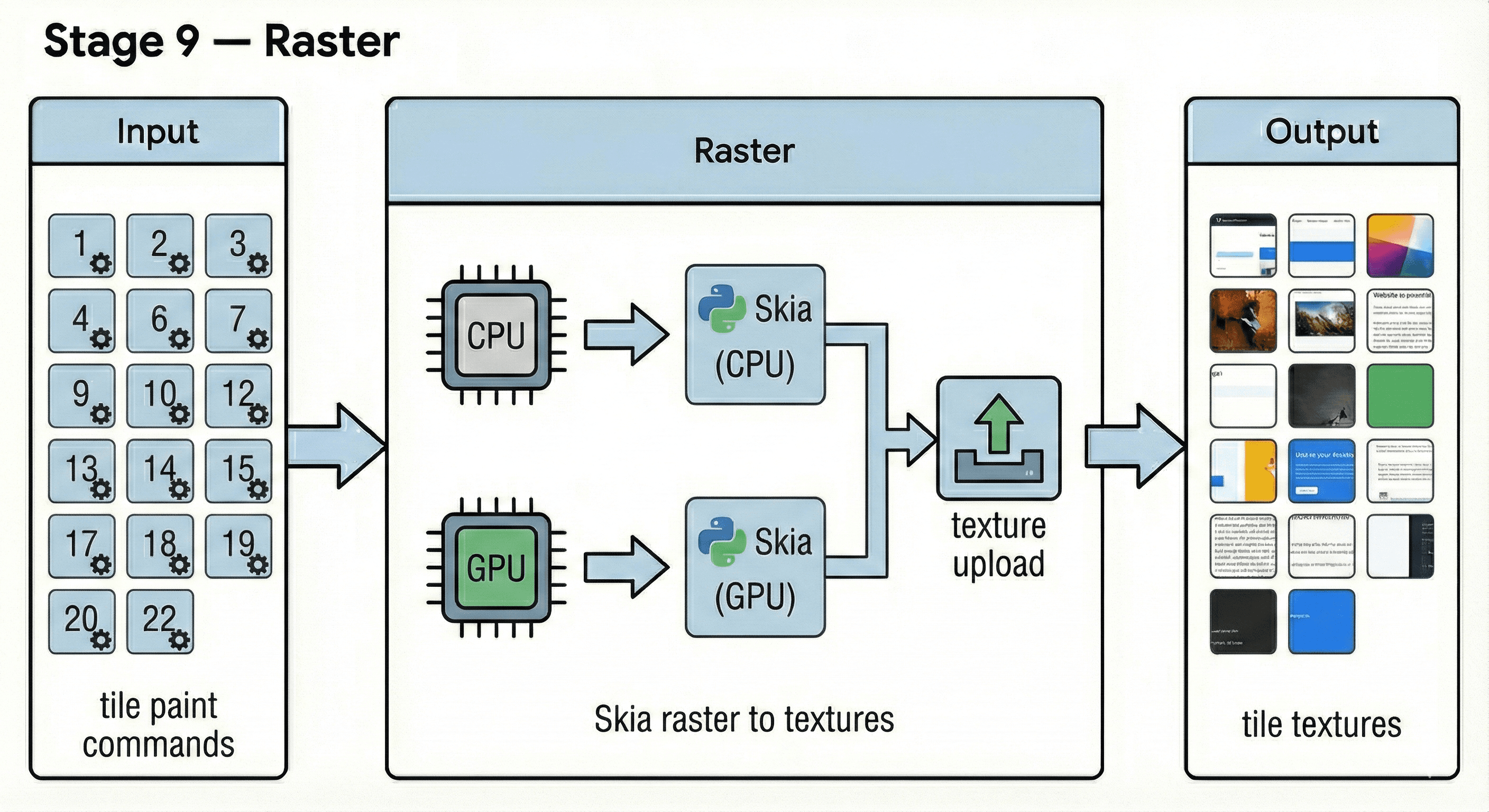

9) Rasterization: tiles’ paint commands → pixel textures (Skia)

Rasterization is where instructions become pixels.

Input:

display list / paint commands

tile boundaries

What happens:

Skia turns paint commands into pixel data for tiles

Often done on GPU (platform-dependent)

Newer Chrome work includes Skia Graphite as a modern GPU backend (successor direction beyond Ganesh), optimized for modern low-overhead APIs.

Output:

Rasterized tile textures (pixel data in GPU resources)

Raster

Rasterization replays draw commands for each tile to generate pixel textures (CPU and/or GPU paths).

Skia performs the raster work; results may require texture allocation and upload to GPU memory.

Expensive visual effects or large invalidated areas can make raster the bottleneck even when JS is fine.

The output is tile textures used by the compositor to assemble the final frame.

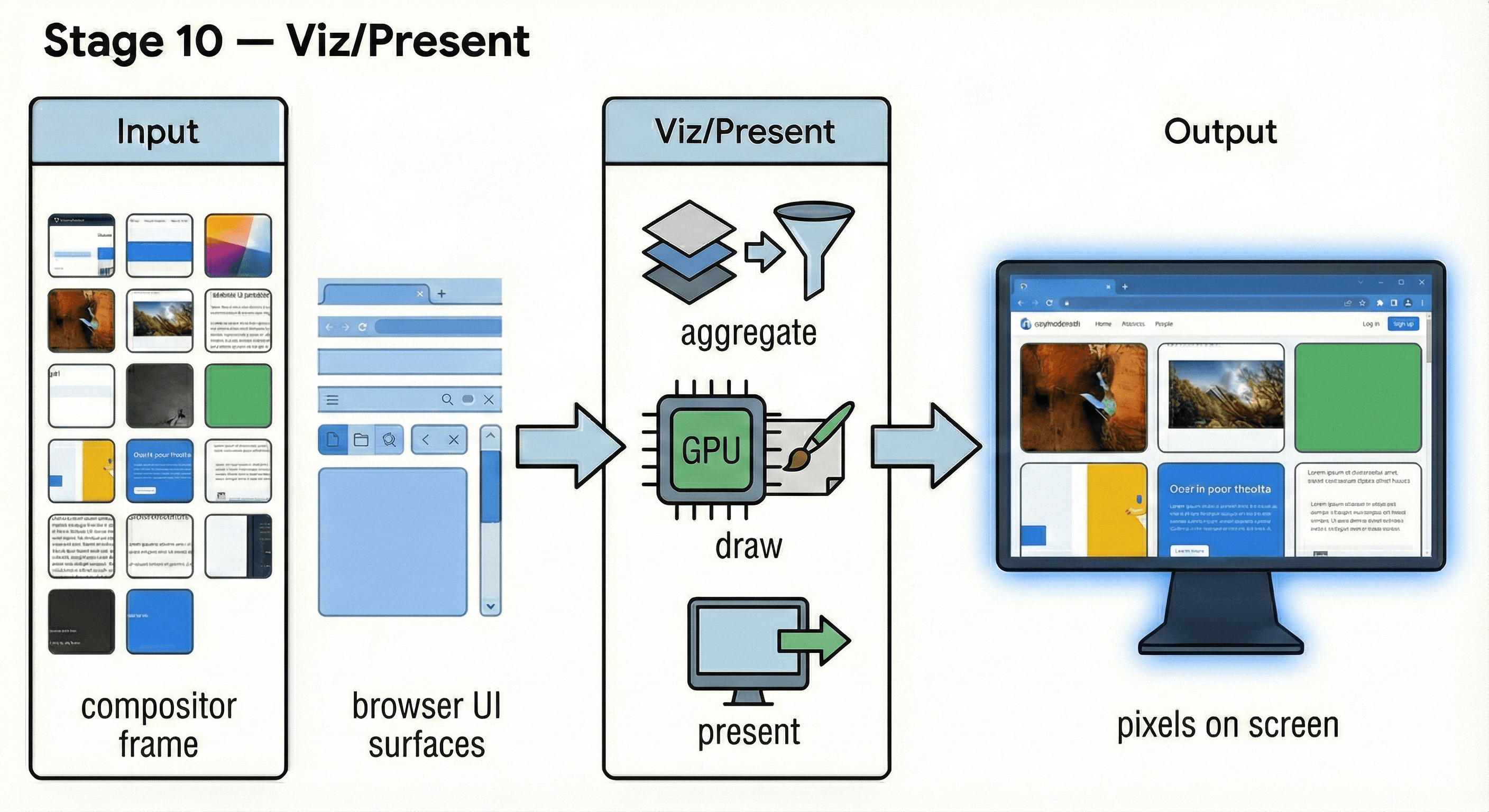

10) Submit → Aggregate → Present: Viz draws the final frame

Input:

One or more CompositorFrames from renderers

Browser UI surfaces

What happens:

Viz aggregates frames (tab content + browser UI + possibly cross-process iframes)

Schedules the final draw

Presents the result to the OS compositor / display

Output:

Pixels on screen (a presented frame)

Viz/Present

A compositor frame is a structured description of the frame (passes/quads/surfaces), not a single bitmap.

Viz aggregates frames from the page and browser UI, then coordinates GPU work and presentation.

Presenting involves synchronizing with the platform compositor/display timing (vsync) to show pixels.

The output is the final pixels on screen.

The pipeline is conditional: what changes trigger what work?

A key performance insight: not every update runs every stage.

Some updates affect style only

Some require layout (geometry changes)

Some require paint/raster (pixels change)

Some can be handled mostly in compositor (e.g., transform/opacity animations when already painted)

This is why “make animations compositor-friendly” is practical advice — it’s about skipping expensive main-thread stages when possible.

Debugging & verification: what to look at in DevTools

If you want to prove your mental model:

Performance panel

Record an interaction (scroll, click, animation)

Look for time in:

Recalculate Style

Layout

Paint

Composite / Compositor work

Identify long tasks on the main thread

Rendering tools

Paint flashing (see repaints)

Layout shift regions (CLS)

Layer borders / tiles (understand composited layers and tiling behavior)

Layers panel

Explore composited layers and how the page is split for compositing.

Common misconceptions (and the correct mental model)

“Paint means pixels are drawn.” No — modern browsers paint-record draw commands first (a display list). Rasterization is where those commands become pixels.

“GPU acceleration makes everything faster.” The GPU is great for compositing and raster, but you can still bottleneck on the main thread (JS, style, layout, paint recording). Also, too many composited layers can increase memory and management overhead.

“Changing CSS is cheap if it’s ‘just visual’.” Some visual changes trigger paint (or worse, layout). The cost depends on what you change and how often. The rule of thumb is: avoid patterns that cause frequent style recalculation + layout + paint every frame.

“Layout happens once.” Layout can rerun often due to DOM mutations, viewport changes, font loading, or forced synchronous layout (a.k.a. layout thrashing) caused by interleaving reads/writes of layout-dependent properties.

“If scrolling is janky, it must be rendering.” Sometimes it’s actually long JS tasks blocking input handling (high INP), heavy event handlers, or synchronous work triggered by scroll listeners.

“CSR vs SSR is mainly about SEO.” SEO is part of it, but the bigger trade-offs are time-to-first-render, hydration cost, caching strategy, interactivity timing, and operational complexity.

Debugging checklist (symptom → DevTools evidence → likely stage → what to try)

Use this when something “feels slow.” The goal is to classify the bottleneck first, then optimize.

Symptom | DevTools evidence | Likely stage | What to try |

Click feels delayed / UI freezes | Performance shows Long Tasks on main thread; INP is high | JS / main thread | Break up long tasks, defer non-critical work, use requestIdleCallback (carefully), reduce heavy sync work in event handlers, avoid expensive re-renders |

Animation/scroll drops frames | Time spent in Recalculate Style / Layout / Paint each frame | Style/Layout/Paint | Avoid layout thrashing (batch reads then writes), reduce DOM size, simplify layout, animate transform/opacity where possible, use containment ( |

Visual changes repaint huge areas | Enable Paint flashing → large regions flash; Paint time high | Paint | Reduce expensive effects (blur/shadows), avoid repainting large fixed backgrounds, isolate elements, consider compositing for isolated animations (judicious |

Smooth scroll but content looks blurry then sharp | Raster tasks appear; tiles update after scroll; “checkerboarding” | Raster/Tiling | Reduce paint complexity, avoid huge paint areas, ensure GPU raster is enabled, reduce overdraw, use simpler effects, prefer smaller images near viewport |

First content appears late | Network waterfall shows late critical resources; LCP element loads late | Network + render blocking | Preload critical CSS/fonts, reduce render-blocking JS, optimize server response, enable caching/CDN, compress assets |

Layout shifts (page jumps) | CLS warnings; “Layout Shift Regions” highlights | Layout + late resources | Add width/height to images/iframes, reserve space for ads/components, avoid injecting content above fold, use font-display strategies |

Hydration feels slow (Next.js) | CPU time after initial HTML; scripting heavy; main thread busy | Hydration/JS | Reduce client JS, split bundles, avoid over-hydrating, use server components where appropriate, lazy-load non-critical UI |

Only one element update causes lots of work | Large “Recalculate Style” or “Layout” for small changes | Invalidation scope too big | Reduce global style churn, avoid changing class on high-level containers, reduce expensive selectors, use more targeted DOM updates |

Scroll handlers cause jank | Main thread busy during scroll; scroll event handlers heavy | JS on scroll path | Prefer passive listeners, throttle/debounce, move work off scroll path, use IntersectionObserver instead of scroll polling |

Quick triage rule:

If the main thread is saturated → optimize JS and rendering work triggered by JS.

If layout/paint dominates → reduce layout/paint triggers and complexity.

If raster dominates → simplify paint, reduce effects, help tiling/raster workload.

If network dominates → prioritize critical resources and caching.

Glossary

Blink

Chrome/Chromium’s web rendering engine:

parses HTML/CSS

computes style

runs layout

records paint commands (And cooperates with V8 for JS.)

cc

Not “CC” as in an acronym you must memorize — it’s the Chromium compositor subsystem living under //cc in the source tree. It owns:

compositor scheduling

layer trees / property trees usage on the compositor side

producing CompositorFrames (RenderPasses + DrawQuads) and submitting them to Viz.

Viz

“Visuals” — the display compositor and GPU presentation service. It aggregates compositor frames (from renderer(s) + browser UI) and presents the final result.

RenderingNG

“Rendering Next Generation”: a multi-year modernization of Chrome’s rendering architecture focused on performance, correctness, and predictability.

LayoutNG

The modern layout engine architecture in Blink that produces an immutable fragment tree as layout output, enabling better caching and incremental updates.

CAP (CompositeAfterPaint)

A RenderingNG project that moved layerization/compositing decisions to after paint. It disentangles compositing from style/layout/paint for more predictable behavior.

Property trees

Separate trees (transform/clip/effect/scroll) that describe how content is transformed/clipped/effected/scrolled, enabling efficient compositor updates.

Paint chunks

Groups of adjacent display items that share the same property-tree state. They are key inputs for layerization and invalidation.

Display list (paint recording)

A list of drawing commands (instructions) produced by paint. Not pixels yet.

Rasterization

Turning draw instructions into pixel bitmaps/textures (often GPU accelerated via Skia).

References

RenderingNG overview —

RenderingNG architecture —

https://developer.chrome.com/docs/chromium/renderingng-architecture

Key data structures in RenderingNG (property trees, paint chunks, compositor frames) —

https://developer.chrome.com/docs/chromium/renderingng-data-structures

LayoutNG deep-dive —

BlinkNG deep-dive (includes CompositeAfterPaint discussion) —

//cccompositor README —https://chromium.googlesource.com/chromium/src/+/HEAD/cc/README.md

“How cc works” —

https://source.chromium.org/chromium/chromium/src/+/main:docs/how_cc_works.md

//components/vizREADME —https://chromium.googlesource.com/chromium/src/+/lkgr/components/viz/README.md

“The Rendering Critical Path” —

https://www.chromium.org/developers/the-rendering-critical-path/

Inside look at modern web browser (multi-process overview) —

Chromium Blog: Skia Graphite (rasterization backend evolution) —

https://blog.chromium.org/2025/07/introducing-skia-graphite-chromes.html

Chrome DevTools Rendering tools —