Where your Chrome tab’s “aliveness” really comes fromWhen a Chrome tab feels “alive” (scrolling, clicking, animations, network updates), what you’re really watching is a scheduler keeping the renderer’s main thread from turning into chaos.

That scheduler is the combo of:

Event loop: the loop that keeps picking “the next unit of work”

Task (macrotask) queues: where those units of work wait

Microtask queue: urgent follow-ups that must run before the loop moves on

This post answers the “where does it live?” questions, clarifies whether rendering is a macrotask, and ties everything into the end-to-end pipeline—from bytes to pixels.

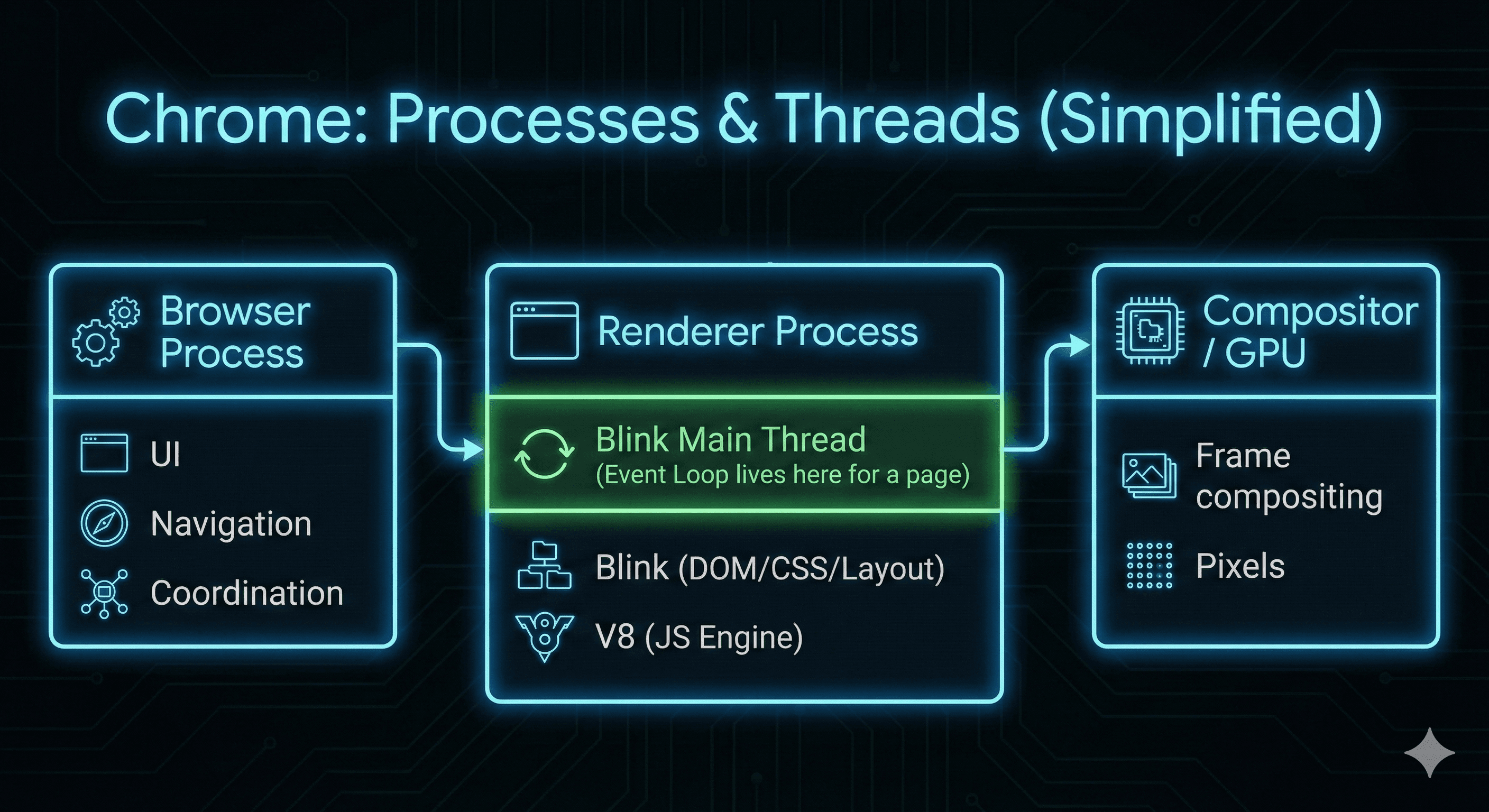

1. Big picture: processes & threads (where your “runtime” actually exists)

Chrome uses a multi-process architecture. For a typical page:

Browser process: UI, navigation, coordination

Renderer process (per site instance): runs Blink + V8 for the page

Compositor / GPU: produces frames (often on separate threads/processes)

Inside a renderer process, there’s a Blink main thread that “runs most of Blink” (DOM, style/layout coordination, and JS execution integration). Rendering also involves compositor interaction. That Blink main thread is where the event loop story matters most.

Chrome: Processes & Threads (Simplified)

2. A better mental model: one thread, multiple “executors”

On a page, a lot of work must happen on the renderer main thread (Blink main thread). Chromium’s threading/task docs describe that most threads have a loop pulling tasks from a queue and running them. Blink’s scheduler doc also frames the main thread as crowded with many “clients” scheduling tasks into the main-thread message loop.

Think of the main thread as:

Event loop + scheduler: chooses what to run next

Executors (what actually runs during a task):

Blink/DOM/CSS engine code (native C++)

V8 JS execution(when a task calls into JS callbacks)

Rendering update steps (native C++ coordinating style/layout/etc.)

Key point: the “call stack” you usually mean is the JS call stack, which only exists while V8 is running JS. But the thread is still executing native code before/after that.

3. The event loop is a host scheduler, not a JS feature

JavaScript (the language) doesn’t define the event loop.

The host environment defines it:

In the browser, the HTML Standard defines event loops, task sources/queues, microtask queue, and the rendering opportunity / “update rendering” scheduling.

In Node.js, Node’s runtime (with libuv) defines an event loop that enables non-blocking I/O by offloading work when possible.

So: V8 does not “have” the event loop. V8 is the JS engine that the host calls into when a task needs to run JS.

3.1 Where is the event loop running (in Chrome)?

Spec view: an event loop is associated with a “relevant agent” (e.g., a Window or Worker global). The spec is abstract about OS threads.

Chrome practical view: for a normal page, the “window event loop” is effectively driven by the renderer process’s main thread message loop / scheduler (Blink main thread). Chromium docs describe posting and running tasks on the “Main Thread in a Renderer Process.”

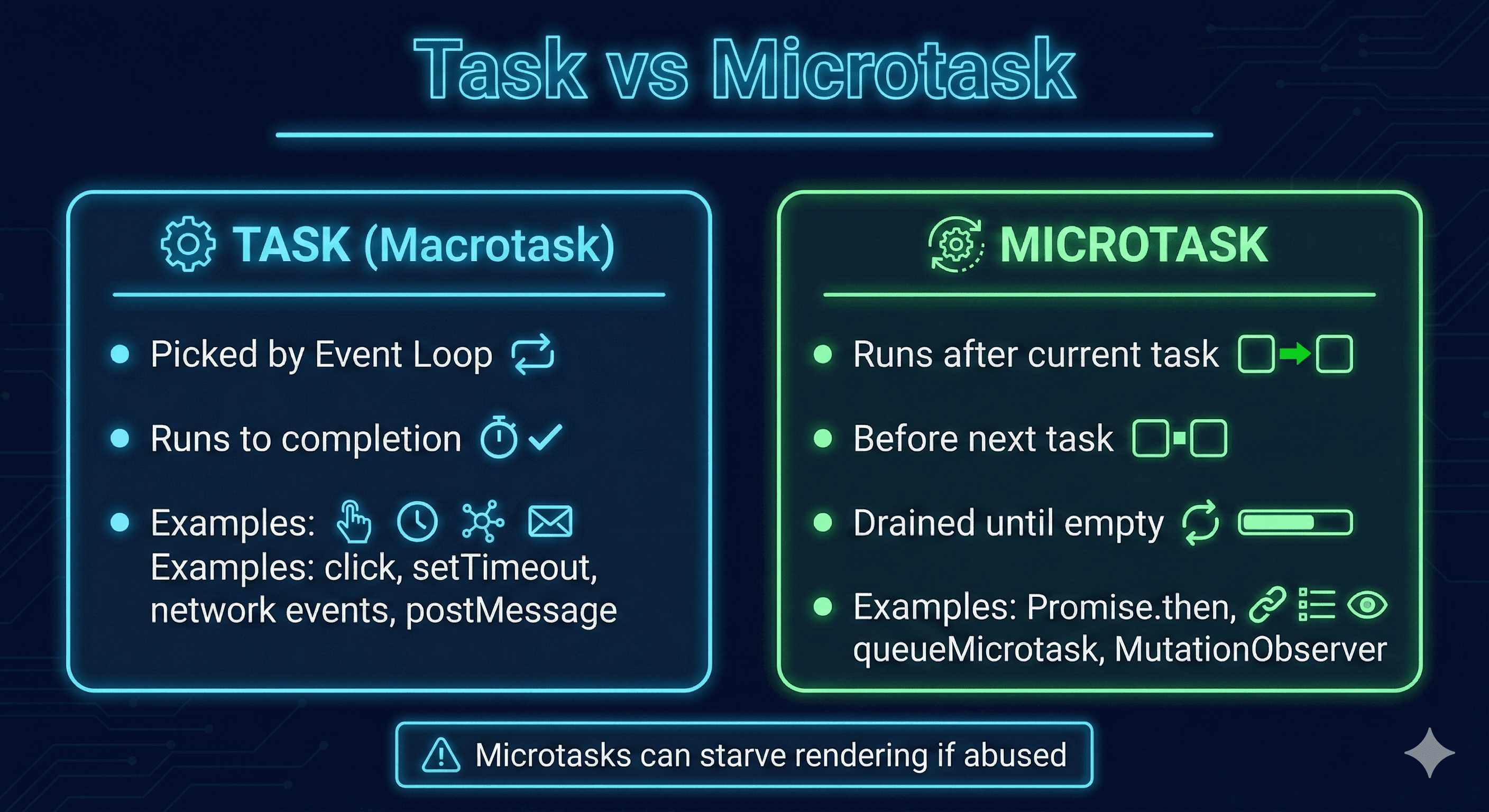

4. What exactly is a “macrotask”?

In everyday dev talk, people say macrotask. In the HTML spec, it’s just a task.Typical sources of tasks:

User interaction: click, scroll, keydown, pointer events

Timers:

setTimeout,setInterval(when they “mature”)Networking: events/callbacks after a response is ready

Messaging:

postMessage,MessageChannel, etc.Other browser work that must run on the main thread

Important nuance: rendering is not “just another task” in the same way. Rendering updates happen in a rendering phase that the browser may perform between tasks when there is a rendering opportunity. Tasks are enqueued via task sources, and the event loop chooses tasks accordingly.

Crucial rule: run-to-completion. Once a task starts running on the main thread, the browser cannot “interrupt it midway” to handle something else on that same thread.

4.1 Where are macrotasks stored?

Spec view:

Each event loop has one or more task queues.

Task queues are sets (not strict FIFO queues), and tasks are grouped by task sources (e.g., user interaction, timers, networking).

Chrome implementation view:

“Stored” as C++ scheduler/message-loop data structures attached to the thread that runs Blink.

Chromium docs describe threads continually processing work from a dedicated task queue, and Blink’s scheduler sits in front of the main thread message loop to organize posted work.

So: task queues live with the event loop, and in Chrome they’re effectively maintained by the renderer main thread’s scheduler/message loop machinery.

5. What’s a microtask, and why does it feel “higher priority”?

A microtask is a callback scheduled to run after the current task finishes but before the event loop picks the next task.

Common microtask sources in browsers:

Promise.then/catch/finallyqueueMicrotask(...)MutationObservercallbacks

At the end of each task, the browser performs a microtask checkpoint: it drains the microtask queue until empty, including any new microtasks queued by microtasks. That’s why microtasks often appear to “jump ahead” of timers and events: the event loop won’t move on until microtasks are done.

Pitfall: too many microtasks can delay input handling and even delay painting (you can “microtask-starve” the UI).

5.1 Where are microtasks stored?

Spec view:

Each event loop has a microtask queue (and it’s explicitly not a task queue).

Microtasks are enqueued via “queue a microtask” and are drained at the microtask checkpoint.

Chrome/V8 implementation view:

Promise reactions and related “jobs” are handled through V8’s

MicrotaskQueue, which is associated with V8 contexts (the embedder must keep it alive appropriately).From a web-dev perspective: microtasks run after the current JS finishes and before returning control to the event loop.

So: microtasks are owned by the event loop spec-wise, but implemented partly inside the JS engine (V8) and integrated with the browser’s event loop checkpoints.

Task vs Microtask

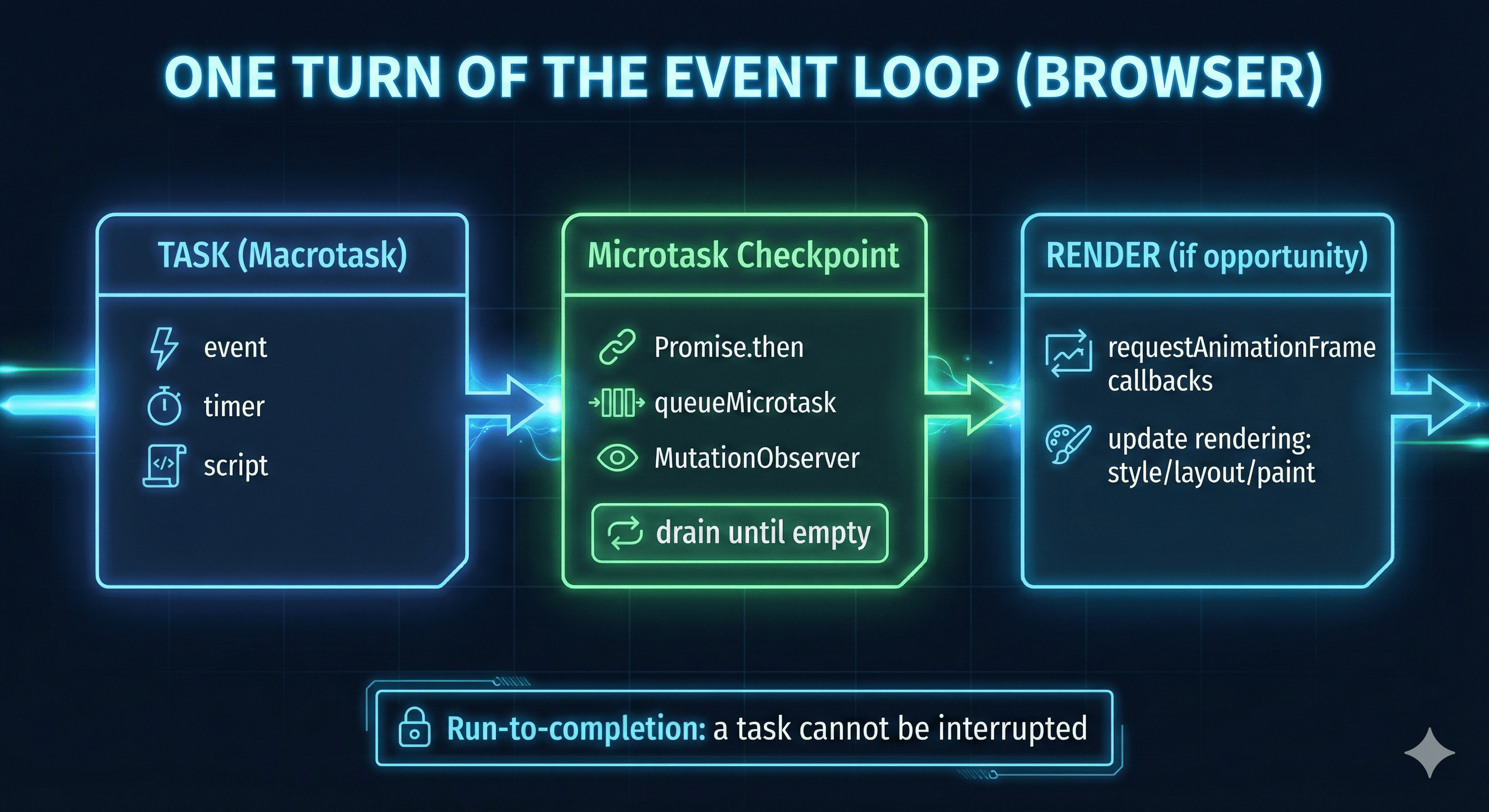

6. The glue: from HTML bytes → V8 execution → event loop → pixels

Here’s the bridge between rendering, JS execution, and scheduling.

A) HTML & CSS arrive (bytes → DOM/CSSOM)

Network fetch occurs off the main thread.

Renderer parses HTML → DOM and CSS → CSSOM.

Script tags and events can schedule JS work to run as tasks.

B) JS runs (tasks enter, V8 executes run-to-completion)

The event loop picks a task (e.g., “run script”, “handle click”, “timer fired”).

That task runs JS in V8 run-to-completion (source → AST → bytecode → optimized machine code).

C) Microtask checkpoint (Promises/MutationObserver flush here)

When the task finishes, the engine/browser runs a microtask checkpoint and drains all microtasks.

D) Rendering update (frame-aligned “update rendering”)

If there’s a rendering opportunity, the UA queues/runs “update the rendering” from the rendering task source (rAF callbacks, then update steps).

Compositor/GPU produce pixels; compositor and renderer main thread coordinate.

One Turn of the Event Loop

7. A concrete ordering example (tasks vs microtasks vs rAF)

Try this:

console.log("A: script start");

setTimeout(() => console.log("D: timeout"), 0);

Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log("B: promise then"));

queueMicrotask(() => console.log("C: queueMicrotask"));

requestAnimationFrame(() => console.log("E: rAF"));

console.log("A: script end");Typical output ordering:

A: script start

A: script end

B: promise then

C: queueMicrotask

E: rAF

D: timeout

Why:

The whole script is one task.

Promise reactions +

queueMicrotaskgo to the microtask queue, drained at the checkpoint.requestAnimationFrameruns in the rendering phase before paint.setTimeout(..., 0)schedules a future task —never “immediate.”

8. Deep dive: how setTimeout behaves in modern Chrome

8.1 Timers don’t go straight into the task queue

Conceptually, the browser keeps timers in a timer structure. When a timer’s delay has elapsed, its callback becomes eligible and is queued as a task.

8.2 Minimum delay + “nested timer clamping”

Even if you pass 0, it means “as soon as possible, after current work.”Also, after 5 nested timeouts, browsers enforce a minimum 4ms delay (per HTML spec).

8.3 Background tab throttling (older materials are often outdated)

Chrome can heavily throttle timers in background/hidden pages to save battery/CPU. Chrome has shipped “intensive throttling” and multiple throttling levels with conditions.

Note: throttling behavior can change across Chrome versions and device power modes—avoid relying on a single rule of thumb.

8.4 Max delay overflow

Browsers store timeout delays in a 32-bit signed integer; values > 2147483647ms (~24.8 days) can overflow and behave unexpectedly.

8.5 this inside timeout callbacks

In browsers, setTimeout(obj.method, 0)calls the function without your object receiver.

In sloppy mode,

thismay bewindowIn strict mode,

thisisundefined

Prefer:

setTimeout(() => obj.method(), 0);

// or

setTimeout(obj.method.bind(obj), 0);8.6 requestAnimationFrame vs setTimeout: why rAF animations look better

How requestAnimationFrameworks: requestAnimationFrame(cb)asks the browser to call cb before the next repaint. The callback receives a high-res timestamp.

Why rAF is better for animation than setTimeout(…, 16):

Frame-aligned: rAF callbacks are scheduled around the browser’s rendering cycle.

No accidental double work per frame: timers can fire at awkward times (too early/late), causing missed frames or extra layouts.

Auto-throttling: when the page is in the background, rAF pauses/throttles naturally, avoiding wasted work.

Minimal animation loop:

let start;

function animate(t) {

if (!start) start = t;

const progress = t - start; // ms

const x = Math.min(progress / 500, 1) * 300; // 0..300px in 500ms

box.style.transform = `translateX(${x}px)`;

if (x < 300) requestAnimationFrame(animate);

}

requestAnimationFrame(animate);9. XHR (XMLHttpRequest) deep dive

XHR is an older but still important API for understanding “host async → callback task.”

9.1 How it works conceptually

Create XHR object

Register callbacks (

onreadystatechange,onerror,ontimeout, etc.)Call

open(...)and set options (headers,responseType, timeout…)Call

send(...)

As the network progresses, XHR fires events like readystatechange when readyState changes.

9.2 Where does the callback run?

Network work is not performed by the JS thread. When progress happens, the browser enqueues a task to dispatch XHR events. That task runs on the main thread; if your handler is JS, it enters V8 and runs on the JS call stack.

9.3 Example XHR with key events

const xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.open("GET", "/api/data", true);

xhr.responseType = "json";

xhr.timeout = 5000;

xhr.onreadystatechange = () => {

if (xhr.readyState === 4) {

console.log("status:", xhr.status, "body:", xhr.response);

}

};

xhr.onerror = () => console.log("network error");

xhr.ontimeout = () => console.log("timeout");

xhr.send();9.4 Common pitfalls

CORS: cross-origin requests require correct server headers.

Mixed content: HTTPS pages loading HTTP resources are restricted/blocked.

(In modern code you’ll usually prefer fetch, but XHR is still a great “event loop anatomy” example.)

10. Promise deep dive: why .then()feels special

Promises solve two problems:

avoid callback pyramids

centralize error handling (chaining + “bubbling” to

.catch())

10.1 Promise callbacks run asynchronously

Callbacks added with then()will not run before completion of the current “run” of the JS event loop. In browsers, Promise reactions are scheduled as microtasks (which is why they run before timer tasks).

10.2 Example: Promise chain + error bubbling

doThing()

.then(result => doNext(result))

.then(final => console.log("final:", final))

.catch(err => console.error("caught:", err));If doNextthrows or returns a rejected promise, the error propagates to .catch().10.3 A useful ordering demo

Promise.resolve()

.then(() => console.log("microtask 1"))

.then(() => console.log("microtask 2"));

setTimeout(() => console.log("task: timeout"), 0);The microtasks drain before the timeout task runs.

11. async/await deep dive: “Promises with readable control flow”

async functions always return a Promise, and await suspends execution until the awaited Promise settles.

11.1 The key scheduling truth

When you await a Promise:

your async function suspends,

when the Promise settles, the continuation is scheduled (in browsers, via the Promise/microtask mechanism).

11.2 Example: why await yields

(async () => {

console.log("1");

await 0; // effectively awaits Promise.resolve(0)

console.log("3");

})();

console.log("2");Typical output:

1

2

3

Because the continuation happens after the current synchronous code finishes, via microtasks.

Note: some older materials claim async/await “uses generators internally.” That can be an implementation strategy, but it’s not required. What matters is the observable semantics: suspend now, resume later.

12. The “long task” problem and modern ways to yield

A long task is commonly defined as main-thread work that blocks for 50ms or more, which harms responsiveness and input latency.

12.1 Why long tasks hurt

While a task is running, the browser can’t interrupt it to respond to input.

12.2 Fix patterns

Chunk work (process N items, yield, continue)

Move CPU-heavy work to Web Workers

Prefer rAF for animation loops (frame-aligned updates)

12.3 Modern yielding: scheduler.yield()/ scheduler.postTask()

The Prioritized Task Scheduling API provides scheduler.postTask()and scheduler.yield().

A practical yield helper with fallback:

async function yieldToBrowser() {

if (globalThis.scheduler?.yield) {

await scheduler.yield();

} else {

// fallback: yield via a new task

await new Promise((r) => setTimeout(r, 0));

}

}

async function processInChunks(items) {

for (let i = 0; i < items.length; i++) {

heavyWork(items[i]);

if (i % 50 === 0) {

await yieldToBrowser();

}

}

}13. How to see the event loop in practice (Chrome DevTools)

13.1 Performance panel: find tasks, long tasks, and rendering work

In DevTools → Performance, record an interaction:

The Main track shows a flame chart of main-thread activity.

A red triangle on a Task indicates a long task.

13.2 How to read it

Stacked frames indicate “who called whom” (native + JS).

You’ll often see clusters like:

Task → Function Call (JS) → Layout / Recalculate Style / Paint

This is where your “JS → rendering” glue becomes visible.

References

Event loops:

https://html.spec.whatwg.org/multipage/webappapis.html#event-loops

Perform a microtask checkpoint:

https://html.spec.whatwg.org/multipage/webappapis.html#perform-a-microtask-checkpoint

Update the rendering:

https://html.spec.whatwg.org/multipage/webappapis.html#update-the-rendering

Microtask guide:

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/HTML_DOM_API/Microtask_guide

queueMicrotask():

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Window/queueMicrotask

In depth:

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/HTML_DOM_API/Microtask_guide/In_depth

Header (Chromium Source):

https://source.chromium.org/chromium/chromium/src/+/main:v8/include/v8-microtask-queue.h

Header (V8 repo mirror):

https://chromium.googlesource.com/v8/v8/+/refs/heads/12.7.50/include/v8-microtask-queue.h

V8 blog (async/microtasks context):

setTimeout():

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Window/setTimeout

Timer throttling in Chrome 88:

https://developer.chrome.com/blog/timer-throttling-in-chrome-88

XMLHttpRequest:

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/XMLHttpRequest

readystatechange event:

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/XMLHttpRequest/readystatechange_event

Using promises:

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Guide/Using_promises

await:

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Operators/await

Optimize long tasks:

MDN overview:

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Prioritized_Task_Scheduling_API

Scheduler interface:

scheduler.postTask():

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Scheduler/postTask

scheduler.yield():

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Scheduler/yield

Spec (WICG):

Chrome blog:

Analyze runtime performance:

Performance features reference:

https://developer.chrome.com/docs/devtools/performance/reference

Threading and Tasks in Chrome:

https://chromium.googlesource.com/chromium/src/+/lkgr/docs/threading_and_tasks.md

Task scheduling in Blink:

Blink Scheduler README:

Blink Scheduler (design doc):

https://docs.google.com/document/d/11N2WTV3M0IkZ-kQlKWlBcwkOkKTCuLXGVNylK5E2zvc/edit

Rendering performance:

RenderingNG architecture:

https://developer.chrome.com/docs/chromium/renderingng-architecture

RenderingNG overview:

The Rendering Critical Path (Chromium):

https://www.chromium.org/developers/the-rendering-critical-path/

Inside look at modern web browser (Part 3):

requestAnimationFrame():

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Window/requestAnimationFrame